YouTube ft. Steve Chen – 18 Months That Changed the Internet

This episode takes us back to the earliest days of YouTube, as the founders explain why it was a longshot that succeeded against the odds. When co-founders Steve Chen, Chad Hurley and Jawed Karim left PayPal to start YouTube, it wasn’t even clear that the nascent broadband infrastructure could support playing video in a browser. In a brief period until its acquisition by Google—from its first incarnation as a video dating site to confronting daunting technical and legal challenges—the early story of YouTube is an underdog tale of scrappy upstarts who ended up changing the world.

Listen Now

Key Lessons

The startup story of YouTube was an eventful 18 months that shot a scrappy upstart from idea to cultural force occupying 30% of the internet’s traffic. The journey offers lessons that are still relevant today:

▶ Pair a unique insight with a compelling “why now”: The idea for YouTube built on several underlying trends: photo sharing sites like Flickr had become popular, broadband internet was just coming online, digital cameras with video capabilities were becoming widespread. They also had unique insights: Flash could render videos in a browser despite the device or codec used to create the file; nascent cloud hosting made it possible to deliver video cost-effectively.

▶ Embrace the constraints of the “lean startup” mindset: Being small helped the early team move quickly as they cycled through rapid product iterations and network infrastructure experiments to scale the site.

▶ The power of the hacker ethos: The team utilized a patchwork of nascent cloud hosting providers to offload their hosting costs. While ultimately unsustainable, this brilliant, first-of-its-kind move gave them initial scale on a shoestring budget.

▶ Network effects need a flywheel: YouTube became one of the most powerful network effect products ever built. But when the team first launched the product in 2005, no one noticed. Even YouTube needed a way to get their network effect flywheel spinning. Embedding videos on MySpace pages was the initial nudge sent the flywheel into perpetual motion.

▶ Innovating on legal precedent is a painful road: A startup can innovate along many dimensions: product innovation, distribution innovation, business model innovation, etc. The YouTube team learned that innovating on legal precedent is painful. Ultimately the courts vindicated their copyright claim, but not before the legal pressure on the company forced a sale to Google, which would subsequently spend years fighting the case.

▶ Look for deep synergy in an acquisition: Google’s acquisition of YouTube has become the canonical example of a win-win acquisition. The founders chose Google as an acquirer because of the synergy between their product and Google’s mission to organize the world’s information, but also because of Google’s commitment to maintaining YouTube as a brand. Today YouTube accounts for a significant portion of Google’s revenue, and founder Steve Chen says selling to Google is the “best thing” that could have happened to YouTube.

Inside the Episode

The People

Transcript

Chapters

- Introduction

- From PayPal to YouTube: The Genesis of a Digital Revolution

- Solving the Online Video Challenge in 2005

- From Dating Site to Video Sharing Platform

- Getting the Network Effect Flywheel Spinning

- How MySpace and Viral Clips Fueled YouTube’s Early Growth

- Securing Funding and Entering the Spotlight: YouTube’s Rise in 2005

- Innovating With Early Cloud Hosting to Scale YouTube

- Shifting to In-House Infrastructure

- Uncharted Legal Waters

- YouTube’s Turning Point in the Fight for Copyright Agreements

- The Pivotal Decision to Partner with Google

- The Secretive Sale of YouTube to Google

- YouTube Under Google: Copyright Win-Win and the Creator Economy

Introduction

Steve Chen: I just said, “Look, like, I don’t know if this company is going to be around in three to six months. But what I can tell you is that it’s going to be the most memorable three to six months of your life, in your career, working here.

This is the largest, fastest-growing video service out there and whatever it’s going to do, it’s going to be a story—not just for your storybook, but it’s going to be a story of the internet. And, you know, that could be a bad story, a good story, but it will be a story that people will know about.”

Roelof Botha: Welcome to Crucible Moments, a podcast about the critical crossroads and inflection points that shaped some of the world’s most remarkable companies. I’m your host and the Managing Partner of Sequoia Capital, Roelof Botha.

Today’s episode is about YouTube, one of the most important technology platforms of our time. Over 700,000 hours of video footage are uploaded to YouTube every day. By empowering everyone to broadcast themselves and the world around them, it has transformed society.

But back in 2005, when YouTube was founded by Steve Chen, Chad Hurley and Jawed Karim, broadband was just emerging in the United States. It wasn’t clear that the internet could even support video, say nothing of the massive scale we take for granted today. YouTube was a long-shot idea, and initially, almost no one noticed it.

This story is particularly important to me. I met the co-founders when we all worked together at PayPal. After joining Sequoia, YouTube was one of the first startups I partnered with, and it changed the trajectory of my career.

When Sequoia led the initial funding for YouTube, the company comprised just the three founders, and they were working out of Chad’s garage in Menlo Park, a short drive from our office. It was an exciting time for all of us, and for the future of the internet as a whole.

Today’s episode is about YouTube’s early days. In just over a year, leading up to its acquisition by Google, the company confronted crucible moments that would reshape the technology landscape and popular culture itself—all while dodging lawsuits that threatened to kill the business prematurely. This is the startup story of YouTube.

From PayPal to YouTube: The Genesis of a Digital Revolution

Steve Chen: My name is Steve Chen, and I was the Co-Founder and CTO of YouTube.

I came to Silicon Valley in 1999 to join PayPal, and I think I was one of its first 10 employees very early on. I really was driven towards coming into Silicon Valley where technology is kind of combined with just ideas and being able to be created into a product that people use.

Roelof Botha: At PayPal, Steve met product designer Chad Hurley and software engineer Jawed Karim. After PayPal’s meteoric rise, IPO and acquisition by eBay, they began thinking about their next move.

Steve Chen: It was a difficult decision to make at that point about what to, what to do next. I knew that the opportunities to either join another startup just like PayPal or Facebook, or working for a much larger company, much more established and maybe starting a career or even just staying on at PayPal at the time… Those were all options. I was still in my mid-twenties where I said, “Look, like, I’m going to give myself that period of two years,” or, it was about $100,000 of money that I’d saved up from the PayPal days, and I was like, “If I run out, then I’m going to go back and pursue this career path. But I would really be reluctant to do this without at least trying sometime to make a few swings at the plate.” And that was ultimately the reason for me getting fully behind a startup of my own creation.

Roelof Botha: Steve, Chad and Jawed began discussing ideas for a company they could start together.

Steve Chen: I had a lot of experience with Chad working together on many products and features over and over, over a period of time. We had already been working together for over five years.

Roelof Botha: Chad was the consummate designer, and he was actually the person who designed the original PayPal logo and was responsible for a lot of the ease of use and the delightful design elements in the PayPal website. Jawed had also dropped out of school to join the company. And so, I remember him working incredibly hard at PayPal while simultaneously doing night studies to be able to complete his degree.

Jawed Karim: We had been, uh, meeting up for some time, discussing various ideas that we wanted to work on.

Roelof Botha: This is Jawed Karim, one of YouTube’s co-founders.

Jawed Karim: There were a few things happening that were, you know, really, um, significant for the formation of this idea.

So the first thing that comes to mind is the Indian Ocean Tsunami that happened on December 26, 2004. The Indian Ocean Tsunami event was one of the first times I remember where the content recorded by everyday people became really significant. So there were no professional, like, newscasters on site. I was following this event, and it was difficult to find the videos, right? So there would be—some of these videos were spreading on web servers, so you had to download the file first. It would be in some unknown codec, and you might not have the codec installed, so then you wouldn’t be able to play it.

Solving the Online Video Challenge in 2005

Roelof Botha: Remember, this was 2005—most homes in the United States were just getting broadband internet for the first time. The iPhone hadn’t yet launched. Watching and sharing videos online was a slow and byzantine process.

Steve Chen: Many times, videos that were taken in a certain device would not work if you were playing it on a different device. And this was still—this was years before the iPhone, right? And there was still, there was that work there, and you usually had to download additional software. You couldn’t just watch anything inside the browser.

And so, I think like, uh, the real reason about YouTube was still trying to think about what is next?

We did think that video was going to be the next thing, um, that it was just naturally led there in terms of if photo sharing was really catching on. People were used to sharing, uploading photos with one another, but videos was still new. And I think that in many ways it was still, it was still a challenge, whether or not it was even feasible to use internet as the backbone.

We still had to figure out a lot of these sort of technical challenges, right, on just all the different codecs out there. How do you deal with this? How do you do embedding of a video inside a browser without forcing people to have to download another piece of app to do it?

Jawed Karim: So I remember seeing an ad on some website where they were using Flash to serve up a video. And I was really blown away by that because I had never seen that before. And I didn’t even know that Flash could play videos.

And as soon as I saw that, I thought, “Wow, this could really solve the whole problem with these video codecs, with all these different video formats.” And that was sort of the spark. You know, what if we had a site where anyone could upload videos and you could serve the videos with Flash?

From Dating Site to Video Sharing Platform

Roelof Botha: Meanwhile, along with the expansion of broadband, digital cameras with native video recording capabilities were becoming widely accessible and cloud infrastructure was just beginning to take shape. This gave YouTube the perfect ‘Why Now?’ But the founders’ initial idea was to target a very specific vertical.

Steve Chen: We weren’t as bold to say we were going to become the video platform for the entire internet. There was a service called HotOrNot.com and it was just people uploading photos of themselves. And I think if you were to visit the site as a visitor, you had two choices when you saw a photo: you had the ability to vote up on hot and vote down or not, and the next photo would come in and hot or not.

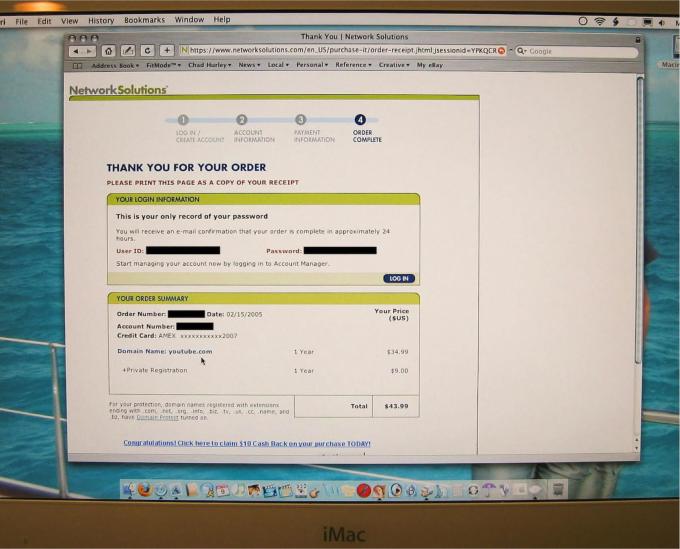

We just thought, “Oh, well, why don’t we just do a video version of this service, this site?” And so, we came up with it. I think it was on Valentine’s Day in 2005 when we actually registered the domain for YouTube.com.

Jawed Karim: The first version was a dating site. And so, the interface was completely different from what you see today. You cannot really, uh, choose the video that you’re being shown, right? So you see a random video, you have to rate the video 1 to 10, and then you see the next video.

Steve Chen: But after we did all this and launched the service in around May of 2005, we released it. And yeah, a week went by, and zero videos were uploaded. So the dating site lasted for one week before we made the change to YouTube as it stands today.

Jawed Karim: So Flickr was probably the biggest photo-sharing site at the time. We decided, “Hey, you know what? Instead of being like the Hot or Not for video, we’re just going to be, let’s say, Flickr for video.”

Steve Chen: I think like, the good decision there was, “Okay, like, instead of giving up, why don’t we give this another try? Instead of it being focused on dating videos, let’s just open it up completely to any video that you want to upload and you want to share.” But even when you make it more generalized to say any types of videos, it’s not like as soon as we made that change we saw a huge acceleration of growth.

Getting the Network Effect Flywheel Spinning

Roelof Botha: The concept of “going viral” is so synonymous with YouTube that it’s hard to imagine now, but even after an early pivot from a dating site, initially, it was crickets—no one noticed.

Jawed Karim: It was not an overnight success. I was working on the site, and I would tail the access log, meaning it would display like the most recent hit on the web server. And I remember tailing this log, and there would be absolutely no records for 24 hours. So there were many days where not a single person on the internet, not even us—not, not even the three of us—would go hit the site. So it felt a little bit demoralizing at the time. Like, okay, how is this possible? Like we have all these videos. I think it’s a cool idea, but basically not one person on the planet has looked at this in the last day.

Roelof Botha: In business, there’s a principle known as the “network effect”—the more participants are connected to a network, the more valuable it becomes. Early on, the founders faced a crucible moment: How could they get anyone to start using YouTube in the first place to get the network effect started?

Roelof Botha: One of the analogies I often gave people at this time was with a consumer product: it all needs to hang together. It’s a little bit like listening to a piece of music.

If 95 percent of the notes are correct, it sounds awful. You know, a painting that just has a few brushstrokes in the wrong places, and suddenly it’s not a masterpiece anymore.

Steve Chen: The atmosphere that we tried to create inside YouTube is that if you have an idea, present it, and we’ll try it out and let’s see what sticks on the wall. We would just launch all sorts of things.

Like, I mean, uh, I remember, like, working all night on a feature where—it doesn’t exist anymore—but it’s like video responses where you end up liking this video so much, you end up having a response to the video. You almost have, almost a conversation that, that happens where each person that speaks is in the form of another pre-recorded video. It doesn’t exist today, but it’s an example of like, look, that was just, um, one of the engineers that had this idea that thought, and we said, “Yeah, let’s, we don’t know. Let’s, let’s try it. Let’s give it a shot.”

Roelof Botha: Over time, the company iterated with lots of other ideas. I mean, one simple one is the video would play automatically. As soon as the page loaded, you didn’t have to move your cursor and go click a play button. It seems like such a small feature, but it’s all these little things that the company did that all together summed up into a delightful experience for users.

How MySpace and Viral Clips Fueled YouTube’s Early Growth

Roelof Botha: Eventually, the lever that truly unlocked growth was a feature that they’d built at the very beginning.

Steve Chen: The direct embedding of the YouTube video was something that we had built in from day one.

This is a new brand that you just created—a new domain that you just registered. In order for you to get this brand out there, you really needed the platforms and foundations that people were already familiar with to be able to want to adopt a new service. And so, we made it so you could put a video in—an embedded video on Craigslist. You could embed a video on eBay.

You could embed a video on any platform that allowed you to insert HTML code at the time. But we still needed a reason for people to want to adopt this new platform and, uh, in 2005 for YouTube that ended up being MySpace.

A lot of people were sending photos, but they didn’t have a way to be able to share videos. What you would do on MySpace, you would encounter one friend that would be showing a video inside their profile. And it would have a YouTube logo, and maybe it’s the first time you’ve seen it. But then maybe five minutes later, you see another friend with another video with the YouTube logo. But by, you know, two, three, four, five days of this, and you start seeing more videos, ultimately, you do click through, and you do go to that YouTube link. And then ultimately, you find other videos that you’re going to watch on YouTube, and you share it. So that virality that YouTube was able to get was really built off of MySpace, but it was done in an organic manner in which we spent zero dollars on actual marketing and advertising, uh, and it was all just built on the consumers and the users themselves, and brandishing, like, what the, uh, the services that YouTube provided for their own needs, and they helped us market the product.

Roelof Botha: The embed feature gave YouTube the initial turn of the flywheel that it needed in order for the network effect to take hold. Over the following months, an active ecosystem started growing.

Jawed Karim: In the early days, there wasn’t, you know, like, one day where it suddenly started taking off, but what would happen is that, suddenly, like, every week we would get, like, some clip that went viral. I think one of the first was—it was this person, like, throwing quarters, um, into a jar on the other side of the room. And that was really impressive.

So it was starting to happen that every week there would be some crazy new, really interesting clip. But just once a week, right? And then it started to happen more often. So then it was like, every three days, every two days. And of course, eventually, every day there would be some amazing new content. So that’s kind of how it took off.

Securing Funding and Entering the Spotlight: YouTube’s Rise in 2005

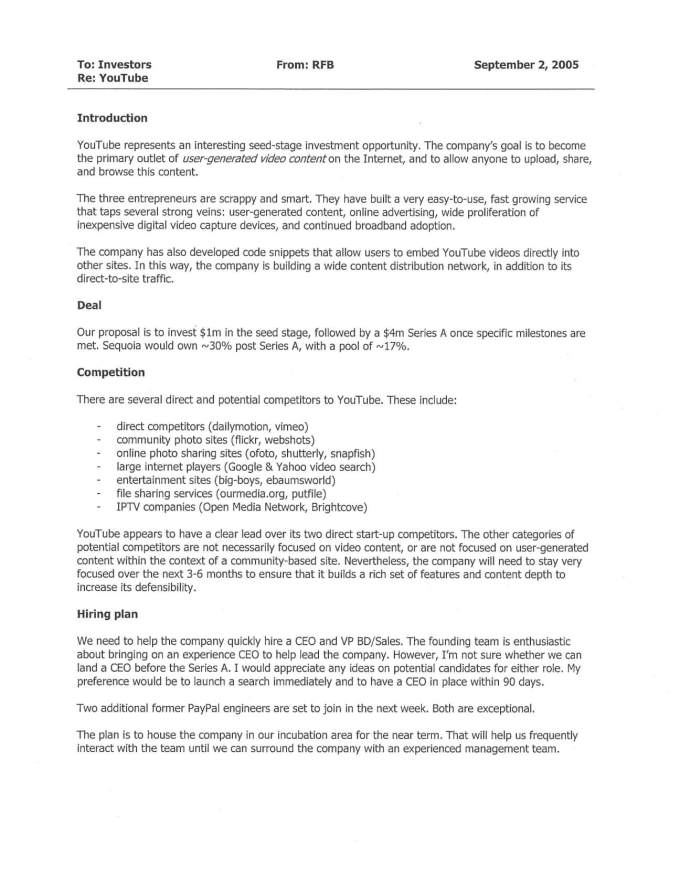

Roelof Botha: In late 2005, less than a year after launch and having found initial traction, the founders went out to raise financing, in part to cover the quickly accelerating costs of hosting and serving videos.

Roelof Botha: Like most investment decisions we make at Sequoia Capital, the decision to back YouTube was controversial. There were few precedents at this point for, uh, consumer internet companies following the dot-com crash, being able to scale successfully and build thriving businesses.

I thought YouTube could become the destination for user-generated video on the internet, that they had a spectacular team and that the product was delightful and easy to use.

Roelof Botha: Soon after we led YouTube’s first financing, and the small team moved into the Sequoia office while they looked for their own space, it became clear that YouTube was scaling at an unprecedented rate. It also found its way into the cultural zeitgeist. It became common to see people huddled around a laptop, watching the latest viral video.

Steve Chen: In 2005, it was this dawning era period of the Internet. There were two big videos that received a million video views. One of them was a Saturday Night Live video clip. And then the another one was—it was a Nike video of, like, Ronaldinho juggling the soccer ball off of a goal post, and I think it was uploaded by a user by the name of Joe B. And so, it seemed like it was, like, a user, but it was actually Nike itself. And we ended up flying up to Oregon to meet up with the Nike team and the marketing team and praise to them to, to even at that time in 2005, to experiment around with different ways of marketing to consumers in a dawning age of Internet videos.

But those two videos, like, okay, there’s something here—that’s about virality of videos.

Innovating With Early Cloud Hosting to Scale YouTube

Roelof Botha: Viral videos became part of the culture, and YouTube views continued to climb. In a surprise move, Jawed left the company to pursue a graduate degree. Meanwhile, Steve and Chad set about recruiting a team to help them build out the platform.

Steve Chen: I was upfront with them to say, “I don’t know if this company is going to be around in three to six months. But what I can tell you is that it’s going to be the most memorable three to six months of your life, in your career, working here.

This is the largest, fastest-growing video service out there, and whatever it’s going to do, it’s going to be a story—not just for your storybook, but it’s going to be a story of the internet. And, you know, that could be a bad story, a good story, but it will be a story that people will know.”

Roelof Botha: YouTube’s growth was exploding. Barely a year old, their challenge was no longer how to get anyone to notice the platform, but how to keep the site from crashing under the strain of new users.

Steve Chen: Those early growth days of YouTube—they’re exciting, and they’re just filled with stories that are still, many of them, the large majority of them are untold.

Much of the growth of the company—it wasn’t so much on the product and engineering side as you would have in many startups where you’re still building more features.

It was still quite a technical achievement to continue to just scale out the service from the back end, from the system side, from the infrastructure side.

We were using up to something like 40 percent of the internet’s bandwidth at that time.

Roelof Botha: This is one of the keys that people didn’t quite fathom at the time was the team had done an incredible job from an engineering point of view to leverage the beginnings of cloud infrastructure. Different early-stage cloud vendors—AWS didn’t yet exist. We were able to leverage third-party vendors for cloud infrastructure, and the company was using open source software to really drive down the cost.

Steve Chen: You had companies back then in 2005 that were trying to kind of out-market and outwit their competitors in the hosting space by saying that we’re going to offer you 2,000 gigabytes of data transfer for free, knowing—at least they thought knowing—that nobody possibly could use 2,000 gigabytes of data transfer on a single machine. There just wasn’t enough, until we came along.

Yu Pan: We were on this, like, a mom-and-pop shop called, like, ServerBeach. And they—they’re a pretty small operation, but we got some kind of deal where we got unlimited bandwidth. And we’re like, “Oh my God, this is awesome. Let’s take advantage of this as much as possible.”

My name is Yu Pan. My title at YouTube was Senior Software Engineer.

Steve Chen: You have the team behind ServerBeach that were—they were freaking out about, like, who is this startup with seven people or something in Silicon Valley that’s using up not just their entire bandwidth from their data centers, but they had a whole second—like it was supposed to be remaining as like a backup, uh, connection into their data centers. We were using up all of it.

We had a model where anytime we measured as we approached 2,000 gigabytes of data transfer per machine, I just went on and just got another machine, and so, another 2,000 gigabytes, another 2,000, and there’s no way that that was going to be a sustainable model for them. But of course, not their fault, because before YouTube, nobody was pushing out this much amount of traffic.

Yu Pan: When we were looking at the projections, we were going to max them out like in no time, basically. Uh, so that was quite a bit scary. And then, like, the other side was just like, yeah, the cost of this bandwidth. It’s like the building’s on fire, basically.

Steve Chen: Nobody expected a service just to come out of nowhere in 2005 and occupy up, what, the 20-30 percent of the Internet’s traffic in a matter of months, um, and not knowing where it was going to continue to go.

Shifting to In-House Infrastructure

Roelof Botha: YouTube had innovated with managed cloud hosting to get to scale in a cost-effective way. But with the cloud providers crying uncle on the terms they’d originally offered, they faced a crossroads: YouTube would need to build its own infrastructure.

Colin Corbett: As we looked at the future costs of running our infrastructure in managed hosting, the numbers were very concerning.

My name is Colin Corbett, and I was the Director of Networking at YouTube.

One of the things I did when I first joined was to go and sign us up for our first data center so that we would operate our own infrastructure and be able to more closely control the costs.

As a result, we ended up negotiating our own bandwidth, we ended up negotiating our server price, and we also—also—our networking equipment we were able to negotiate down.

Steve Chen: We had to be buying up every one of the machines. You had to be going into the trucks on Saturday, Sunday mornings to pull the machines out of the trucks, bringing them up in the elevators and plugging each one of the Ethernet cables in yourselves.

Power was an issue. Just to power these huge racks of machines, um, you had to know. But the problem back then was, you have to physically order your machines four to six weeks before. You have to be there on the spot at the parking lot when it gets delivered. You have to be the one that actually brings up these 42U racks—these 100-pound racks and machines—and then you have to plug in everything yourself, including network cables, power cables.

Colin Corbett: I joined in January. The data center was ready to accept traffic in March.

Our managed hosting provider couldn’t keep up. Their equipment had effectively failed on us. And so, what was supposed to be this nice, gradual migration was: the website is down. The database won’t be fixed for days.

We need to cut tonight to our equipment. We did our forced migration because we had no other choice.

Roelof Botha: But even as YouTube migrated to its own infrastructure, its unrelenting growth continued to present daunting challenges.

Colin Corbett: So, one example was, we realized we were going to run out of web capacity in a few days. Saturday was always our peak day. And we’d had a new rack of equipment on order for new web servers on order. And we worked with our integrator to get our rack ready. And, you know, it wasn’t due for weeks.

And we convinced them, “Please bring it as soon as you could.” So they got the rack to us, I think, at 6 o’clock on a Friday. And then they dropped it off, and then we wanted to get it positioned and we had our data center ready to do that, but they only had one person on staff. The racks, fully assembled, weighed between 1,600 to 2,500 pounds. And so, we couldn’t get it up the ramp to actually get it to our data center.

So I called Klein, who also was on the team, and he and his wife showed up and we all three pushed it up this ramp to get it to the data center hall so that it could then be, that night, it was bolted down. The network was set up, the systems were imaged and everything was deployed. And so, we actually made it through that night.

Yu Pan: I wasn’t actually, like, really confident for the bandwidth side, at least until it’s like, we got Colin. And I was like, okay, we have a little bit of breathing room now, maybe.

Steve Chen: In so many ways, the 2005–2006 was a period when broadband penetration was just really starting to hit the masses in the US, and it was still on the server side.

I think YouTube was the first case where you really, really needed high network bandwidth, and that required a lot more from the server side than was ever needed before 2005.

Colin Corbett: It was a great team, and we all would, you know, we all relied on each other, and we all worked really well to get the, uh, keep the infrastructure running.

If we hadn’t opened it, I, I think we’d have had a few things. The, uh, I think our hosting providers wouldn’t have been able to keep up in scale.

And the second one there was that, I think the monthly fees from the hosting providers, they would have kept climbing and we would have run out of money sooner.

Uncharted Legal Waters

Roelof Botha: By 2006, YouTube began to focus on generating advertising revenue and building a sustainable business. Their engineering feats meant YouTube could serve videos cost-effectively and earn a margin even with low ad rates, but they immediately found themselves in uncharted legal waters: What were the implications of earning ad revenue on user-generated videos if they contained copyrighted materials?

Zahavah Levine: I joined YouTube as its 23rd employee. On my first day, Steve, one of the founders, handed me a sealed box from Ikea and invited me to erect my desk.

My name is Zahava Levine and I was the General Counsel and Vice President of Business Affairs for YouTube. I was YouTube’s first lawyer.

YouTube reached out to me because I was one of a handful of tech startup lawyers at the time with deep experience with licensing music for online services.

Of the 23 employees, most were under the age of 25. At 37, I often felt like the adult in the room, and at times, I felt like the corporate grandmother.

Steve Chen: In the very early days, we knew that for YouTube as a platform to be able to survive and grow and continue to grow, we needed to find a fair way to work with all the parties that are engaged on the platform. And that included the content creators, uh, that included the content owners, if the content creators were using certain pieces of content that they didn’t create themselves.

And then, of course, the advertisers and the marketers that are willing to be able to put their branding and pay for advertising on the platform.

Zahavah Levine: YouTube had just started experimenting with running ads on the site when I joined. But YouTube’s ability to run ads was limited by legal concerns.

Users started uploading videos that contained commercial music in all different ways. Some uploaded copies of official—we called it MTV-style—music videos, but more frequently, users were uploading videos of themselves, either alone or with friends, singing songs or dancing to music playing in the background.

The biggest question for me was whether YouTube could build an advertising-based revenue model without becoming liable for all of the infringing content that users uploaded to the site.

Roelof Botha: So copyright was an important issue out of the gate. This came up as an important issue as we did references before committing to the investment from those who had experienced the Napster episode. We were trying to learn from the mistakes that others had made. Before the financing had even closed, we were already working with attorneys to make sure that we understood exactly what the law provided for to make sure that we did all the right things at the company.

Steve Chen: Napster was one of the first cases where mass adoption about sharing music content on the Internet.

And they took a very aggressive approach in their defense on how they were going to address the, the music labels and the, the, the distributors on what was allowed and not allowed on their platform. And I think that, uh, and from the case of YouTube, I don’t remember the exact dates, but YouTube was after Napster, but we certainly knew about Napster at the time.

And it was, no, like that’s not the model to take.

Zahavah Levine: In 1998, Congress passed a law called the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, or the DMCA. And this law was designed to balance the rights of copyright owners on the one hand, and online service providers on the other.

And the DMCA strikes this balance by providing for a limitation of liability, known as a safe harbor, for online service providers who comply with certain requirements designed to address copyright infringement.

It was clear to me that if YouTube qualified for this DMCA safe harbor, it had the potential to be wildly successful. But if it didn’t, and YouTube could be held liable for copyright infringement for all of the infringing user videos, I couldn’t see how the company could be successful. It, it would all come down to whether YouTube was eligible for this DMCA safe harbor. But the law wasn’t clear on its face. There was a lot of ambiguity.

I called a friend of mine who happens to be one of the world’s great copyright lawyers and I asked for his advice. We met at one of my favorite dive bars in the Mission in San Francisco.

I just asked him, “Will YouTube just face massive lawsuits and get sued out of existence?” He shrugged his shoulders and said, “Who knows?”

On one level, earning any revenue at all entailed some risk for YouTube. Revenue was, quote, “financial benefit” that someone would surely claim was directly attributable to infringement. But if we couldn’t earn revenue, we had no business.

Steve Chen: If we have to be the first movers in figuring this out, what is the way to make everybody happy in this picture?

YouTube’s Turning Point in the Fight for Copyright Agreements

Roelof Botha: YouTube believed it was shielded by the DMCA’s safe harbor clause and that it could create a business model that would be a win-win for creators, copyright holders and itself—but other parties in the entertainment industry did not agree with that interpretation, to put it lightly.

Zahavah Levine: Hollywood were the gatekeepers, and then YouTube opened its own gate and a lot of people walked through it.

The music companies and Hollywood had large anti-piracy teams that were sending us hundreds and, in some cases, thousands of copyright takedown notices a week.

We realized pretty quickly that we would need to close content licenses with the music industry and Hollywood.

Roelof Botha: Although YouTube managed to negotiate deals with companies like Warner Music and EMI, others were strident.

Zahavah Levine: Universal Music Group fully unleashed an orchestrated campaign of fear tactics on us. After months of somewhat friendly negotiations, I remember UMG just suddenly flipped on us.

I recall one exec with, with whom I had previously had a good relationship, literally scream at me over the phone: “YouTube was built on the backs of our artists and owes us hundreds of millions of dollars!”

Roelof Botha: The single worst business meeting of my life was when I flew down to Los Angeles for a meeting with Universal Music.

Zahavah Levine: They put all of their senior heavy lawyers in a conference room, and as soon as the meeting began, they started waving a copy of a lawsuit complaint and demanding tons of money.

Roelof Botha: It really struck me that they were not interested in a win-win relationship with the service and that they would do everything in their power to make our life miserable.

Steve Chen: I mean, they hold all the cards. You have something on your platform that is owned by Universal. And there aren’t that many choices that you could take.

Zahavah Levine: It didn’t take long in this meeting before Chad agreed to pay a big sum of money in exchange for a license agreement we would still need to hammer out.

A sum of money we had no way to pay at the time. I thought that meeting was just awful. I was sure we had substantially overpaid. I was sick to my stomach, and I was worried that other music companies would adopt the same tactics to try to extort crazy amounts of money from us.

Roelof Botha: I had rarely encountered a business experience like this. You know, Silicon Valley just has a very different tone and mentality when it comes to business relationships and a much more of a win-win, let’s build something together attitude.

The idea that you were going to create value, and yes, there is a question about exactly how to divide the pie, but ultimately the goal should be to grow the pie as big as possible.

And the sense I got from my meeting at Universal Music was a fixed mindset: There’s only so much value, and we, Universal, need to do everything in our power to squeeze as much out of this as possible to your detriment. That was a pivotal meeting. Honestly, I think that that meeting really shook us as a team because of the aggression and antagonism that they displayed. It was truly hostile.

Zahavah Levine: I think this UMG shakedown was a turning point.

I think it was a turning point for Chad and possibly Sequoia. I think it helped Chad and Roelof appreciate the gravity of our copyright issues. And perhaps warm up to the idea that selling YouTube to a company that could commit more resources to our legal challenges was not a terrible idea.

The Pivotal Decision to Partner with Google

Roelof Botha: It was now clear that a flood of litigation from rights holders was inevitable. YouTube’s life was on the line. How would this young company be able to handle massive lawsuits from some of the world’s biggest corporations?

There was a potential solution, however, that could not only help protect the company from impending lawsuits, but ensure its longevity. Various companies had shown interest in acquiring YouTube, including Google, whose own video product had failed to catch on with users.

Roelof Botha: Anytime you contemplate the sale of your company, I think it should be called a crucible moment. It’s at this point where the founders, even if they have the ambition to build something enduring that is standalone, they may feel that the company’s future is in better hands with somebody else that can help them realize that ultimate vision.

Unfortunately, oftentimes big companies swallow little companies and, maybe by accident, smother them. They don’t enable them to realize their potential.

Steve Chen: In 2006, a decision had to be made within the board about what our next major step was going to be for YouTube and whether or not that was going to be through an acquisition, or do we continue to operate as an independent company and try to figure all this out ourselves?

And to be honest with you, we were kind of forced down that path of going down the acquisition route with Google. Was really on the, on the legal side of things.

Zahavah Levine: We were just too small. We could barely even hire because everybody was so busy keeping it all together with band-aids.

At that time, it was clear to me that we needed help.

Roelof Botha: I was worried at that time that if we didn’t sell the company, it would be very expensive and time-consuming for us to fight the copyright battles. I had confidence that we would prevail.

But in 2006, you didn’t have the kind of late-stage financing environment that you have today. It wasn’t easy for us to go and raise a hundred or $200 million to fight the lawsuit. And so, and I also think it would have been pretty tricky to go and raise money for the explicit purpose of winning a lawsuit. So I think it was daunting to be able to take on that challenge as an independent business.

Steve Chen: And so, for me, that was a very difficult period. Like, the product was working great. The engineers, we had a great team, but it was really survival of this product of being able to share videos online on the internet space. Is that going to be feasible or not?

Is it time to sell the company in order for YouTube to really, truly reach its potential? It really would benefit greatly to be working in tandem, in collaboration, under the umbrella of a Google, rather than trying to do it independently on its own.

We decided internally, and this was still mostly through Chad and me, to say, like, look, in order for this thing to scale out, we really need a bigger partner and somebody to be able to hand-hold us through this.

The Secretive Sale of YouTube to Google

Roelof Botha: But there was a risk: If the big media companies caught wind of a potential acquisition, they might accelerate the lawsuits they’d been threatening.

Steve Chen: We reached out directly to the board of Google, and we arranged a meeting to talk about and gauge their interest on, look, like we want to move forward with a sale, but we need to move quickly on this. We need to do it in a kind of a furtive, secretive manner because we don’t want it to be known by Universal and EMI that we’re talking to a much bigger company for an acquisition.

Internally deciding that we want to move forward with an acquisition, to talks internally about who potential acquirers could be to meeting with the key individuals in these firms in these companies that can actually make that decision, to actually writing out the actual contractual terms on the, and all the way to finalizing it and making the announcement on Wall Street. All that was compressed into less than one week’s time.

Zahavah Levine: The sale of YouTube to Google has got to be one of the fastest deals of its size of all time. I think it took something like five days from signing the term sheet to signing the long form. And I think it was probably the hardest five days of my life. I was operating on pure adrenaline.

While helping negotiate the merger agreements for the sale of YouTube to Google, two other things were going on. First, we needed to close the three remaining major record label licensing deals that we had been negotiating at that point for months. Google wanted them done before close.

So in three days, we finished these deals that would normally take months.

And on top of that, in addition to negotiating these record label deals, YouTube was moving offices that very same weekend. The move had been planned for months; like, there was nothing we could do to stop it. And I remember Chris Maxey and I were in the office in San Mateo, above Amici’s, at like 2:00 AM on a Saturday morning—um, night-morning—trying to finish the record company deals.

We were sending drafts back and forth with the record companies at like in the middle of the night, and we’d print each draft and mark up our comments in pen. And suddenly, in the middle of all this, our printer stopped working. And we were like, “What’s going on?” And we realized the movers had unplugged it and were, like, packing it up.

And we had to beg them, like, “Sir, I know you’re just doing your job, but please leave the printers. I promise we’re authorized to instruct you to leave the printers.”

It was nuts. I slept for only a few hours the entire time and in a hotel room right next door to our law firm. I didn’t even bother going home. And we got it all done.

Roelof Botha: In November 2006, Google acquired YouTube for $1.65 billion, a staggering sum at the time. Google asked Steve and Chad to stay on to lead YouTube as a stand-alone brand under its umbrella and phased out its Google Video product.

Roelof Botha: I think there was a real meeting of the minds and an appreciation that Google’s interest was in helping YouTube flourish.

And it was clear to the founders that Google had a sincere desire to enable YouTube as an independent business to flourish. They made very clear commitments that the company could retain its independent brand. It wouldn’t be called Google Video. It would be called YouTube. They would maintain a separate office in San Carlos and they wouldn’t all have to move down to Mountain View where Google’s headquarters was based.

And Google also was willing to make the investment necessary to fight the copyright lawsuits that have been filed, and also to invest the infrastructure, the data center infrastructure, to enable YouTube to continue to grow into the scale that it’s achieved today.

Steve Chen: I’m just still grateful the way that Google handled that acquisition, that they still, um, were able to put us in control, to trust a couple of 28-year-olds to run this thing.

Google did a fantastic job in never completely enforcing this Google umbrella over YouTube. They continue to, even till this day, YouTube stays separate in terms of a lot of its reporting structure, organizational structure and even just physical addresses of the buildings. There are YouTube offices, and there are Google offices.

Zahavah Levine: Google had the resources to defer revenue and to take the long view.

Sure enough, just a few months after Google acquired YouTube, Viacom, the major media conglomerate, sued Google, seeking over a billion dollars in damages. They argued that YouTube was responsible for all the copyright infringement of users, who it alleged uploaded over a hundred and fifty thousand clips of Viacom-owned programming without authorization, which had collectively been viewed 1.5 billion times.

This was it. This was the existential lawsuit we all knew was coming. And it got worse, because shortly after Viacom sued, at least two class actions were filed against Google on behalf of sports leagues and music publishers and a class of, quote, “all copyright holders in the world,” unquote. That was, uh, quite something.

YouTube’s sale to Google was the crucible moment that enabled all the subsequent crucible moments that make YouTube what it is today.

Steve Chen: I’m absolutely clear that we made the right decision, to sell it with that amount of time at the time that we did and to sell it to Google.

There was a high risk that YouTube would’ve never made it out of 2006, 2007 if it weren’t for that acquisition with Google.

YouTube Under Google: Copyright Win-Win and the Creator Economy

Roelof Botha: Google not only had the resources to fight the lawsuits against YouTube, but it also supported YouTube as the company deployed systems to instantly identify copyrighted materials posted to the site.

Roelof Botha: One of the unheralded pieces of technology that YouTube built that assured its survival, and honestly, why I think the company has thrived, is copyright ID tags.

Zahavah Levine: With Google’s resources, and while we were litigating the Viacom lawsuit, we worked very hard to build very sophisticated automated systems to accommodate copyright management and content licensing at scale.

With Google’s help, YouTube was able to design and build a Content ID system that was substantially more robust. The system scans each of the millions of YouTube videos uploaded every day against a massive database of sound recordings and audiovisual works provided by copyright owners all around the globe.

And when the system detects a match, meaning that it’s identified third-party copyrighted material in a user-uploaded video, the system honors the rights holders’ choice to either license it, monetize it and share in the revenue, or to have it removed from the site. And, like, an overwhelming majority of the content of the rights holders using the Content ID system elect to license their content and share the revenue on, on YouTube. As far as I know, the YouTube content identification system is the most advanced system of its kind in the world to this day.

Roelof Botha: It’s been crucial. You know, it wins the hearts and minds of copyright holders that know that YouTube is a partner to theirs, not an adversary. YouTube is a valuable distribution partner. It generates revenue that it shares back with these copyright owners.

Roelof Botha: By building a platform to responsibly share revenue with creators and rights holders alike, YouTube would go on to single-handedly bring about the so-called “creator economy,” enabling everyday users to monetize their content.

In 2010, a district court threw out Viacom’s lawsuit, ruling that YouTube was in fact eligible for the DMCA safe harbor and therefore protected from copyright liability.

YouTube is nearly 20 years old, and due to its ubiquity and reach, has shaped some of the most seminal cultural moments of the 21st century.

Steve Chen: One of the most, like, memorable moments for me at YouTube was when we received a call in 2007 from CNN. They wanted to host the Democratic debates for the elections in 2007 at the time, and they wanted to do it using, utilizing and partnering with YouTube, where the questions wouldn’t just be coming from the 2-3 moderators, uh, but it would actually be coming from YouTube users. And that was when I started realizing this is far bigger than something that we created back in 2005.

Roelof Botha: Today, YouTube has over 2.5 billion monthly active users, including more than 100 million paid subscribers. A little over a third of the world’s entire population watches YouTube every month.

Zahavah Levine: YouTube achieved many impressive accomplishments and crucible moments in its early years—the technical infrastructure required to store and deliver an unprecedented volume of video content around the world, the historic licensing deals with the music industry that licensed on a blanket basis for the first time ever entire catalogs of music for use in user-uploaded video.

Steve Chen: It’s not fair to look at the end result of where I am in the finish line of, see where YouTube is, and to see how all this magic happened. I think it’s a lot more realistic to look at where I was in 2005. And when I was there in 2005, it was a video dating service that we thought was going to be the next big thing. Right? And of course, it went through hundreds of cycles of evolution and path turning and turns to be able to get to where YouTube is today.

But in order for it to reach YouTube, to reach to the state that it was at, those first few steps had to be taken from us as the founders and the entrepreneurs of the company.

Multiple generations are watching YouTube as their primary source of entertainment, source of education, source of content globally, all around the world. Um, and people are entirely creating careers, completely just built off of YouTube, the platform.

The key message is that if you have an idea, if you want to start something, I think just don’t ask anybody else. Just, um, especially don’t ask your mom. Like I did, at least once in your life, I just recommend highly trying to do something on your, your own, especially if you do have an idea that’s been brewing in your head for a while, like try it. And you’ll know three to six months, uh, if it’s going to work. And even if it doesn’t work, it’s going to be the most memorable three to six months of your life.

It’s so fun to try to actually create something and an idea that you have. And it’s so entertaining, such a great gift when you actually see other users using this product idea that you had in your head. It’s just hard to be able to get that same kind of return on anything else you do in life.

Roelof Botha: One of the unsung heroes in the YouTube story is Susan Wojcicki, an early Google employee who championed acquiring YouTube and later served as its CEO for nine years, until 2023. Tragically, she passed away in August 2024. Susan’s contributions and stewardship of the brand were critical to YouTube scaling into the global platform it is today.

This has been Crucible Moments, a podcast from Sequoia Capital.

Crucible Moments is produced by the Epic Stories and Vox Creative Podcast Teams, along with Sequoia Capital. Special thanks to Steve Chen, Jawed Karim, Yu Pan, Colin Corbett, and Zahavah Levine for sharing their stories.