Sequoia partnered with Brud in 2017 and in 2021 the company was acquired by Dapper.

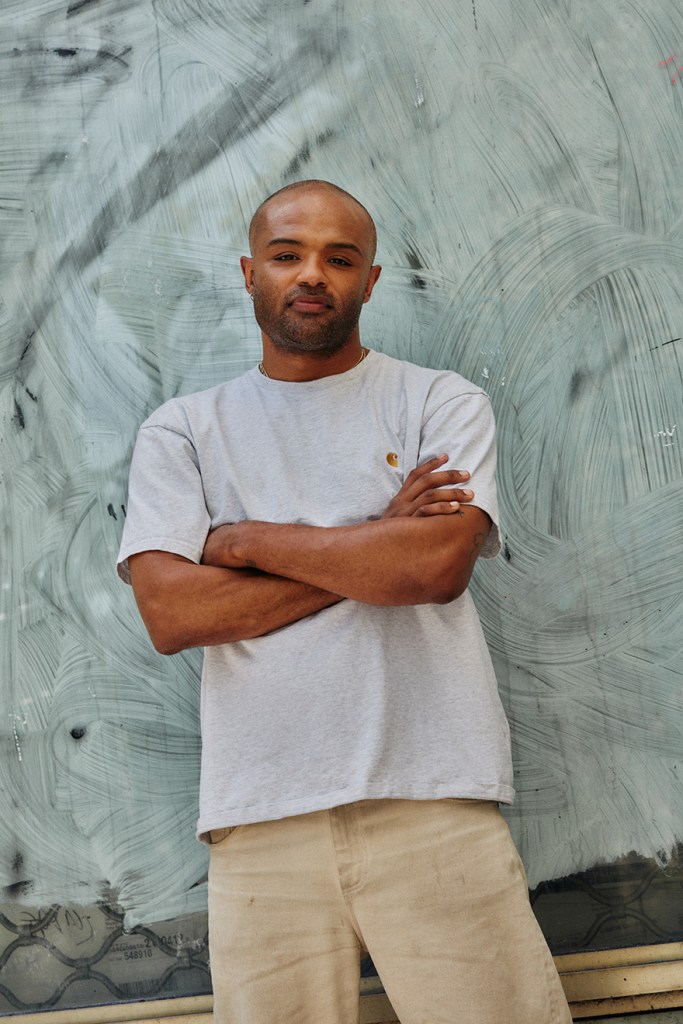

Trevor McFedries’ ’89 light-blue BMW was a mess. Standing at a garage in the West Adams neighborhood of Los Angeles, he was waiting for an update on repairs he knew he couldn’t afford when his phone buzzed. His heart leaped. It was 2017, and this call could change his life. McFedries was almost broke. He’d run through his savings while pitching his big idea to 60 investors who’d gone cold, and one who’d given him a few hundred thousand dollars, which was quickly disappearing into keeping his big idea alive. The caller was Stephanie Zhan, a partner at Sequoia Capital. McFedries hurried into the parking lot away from the shop noise and he started talking.

He told Zhan that he wanted to explode out the opportunities for art and culture to be monetized, changing everything about how creative work is done and who is compensated—from the incentives to create, to the mechanisms for making art, to the distribution of wealth. He would start with his own company, Brud, which he envisioned as a more modern Marvel, where stories are shaped and told by communities empowered to co-produce content and share in the profit, all built on a new version of the web. McFedries told her he based Brud’s first project on his years working as a producer and DJ, collaborating with stars like Katy Perry and Steve Aoki and working at Spotify and JJ Abrams’ production company, Bad Robot: Brud would reinvent celebrity. Not to replace McFedries’ famous friends entirely, but to build a more egalitarian system alongside them.

He already had a solid proof-of-concept for how to do this, he told Zhan. He’d designed a character named Lil’ Miquela, or Miquela Sousa, a 19 year-old creative based in Downey, California, that Brud launched on Instagram in 2016. Her account followed a proven influencer formula: candid selfies of her eating ice cream and going to the movies, and confessional videos talking about falling in love or venting about the challenges of making music. At the time of the parking lot call, it was not totally clear to fans that Lil’ Miquela was CGI. Lil’ Miquela was a modest, mysterious Instagram presence with a sprinkle of freckles and notably full lips. Zhan had heard about her as a low-key phenomenon: Was she real? Was she fake? Did it matter? And why were her bangs such an awkward length?

“I knew from the beginning that Trevor was special—he had a deep understanding of consumer psychology and an instinct for creating pop culture.”

STEPHANIE ZHAN

Awkward was the point, explained McFedries. Lil’ Miquela had been designed anticipating a new kind of relationship between celebrities and the public, one in which a celebrity is aspirational, but the artifice is clear. The bangs are both a signifier of authenticity, like magazine spreads reading, “Stars: They’re Just Like Us,” as well as somehow too perfect and air-brushed. Her ethnically ambiguous look was intended to resonate with a diverse generation that expects to see itself reflected in culture like no previous one. “I knew from the beginning that Trevor was special—he had a deep understanding of consumer psychology and an instinct for creating pop culture,” Zhan says. “He was often ahead of the game, and always had a sense for what was next.”

What was next, according to McFedries, was actually going to be two innovations. The first was this new kind of celebrity. McFedries saw, and still sees, some celebrities as auteurs, with powerful new ideas, but he also sees many celebrities as the center of an ecosystem in which the real value comes from the edges: songwriters, designers and writers. But celebrities, and the companies they work with, keep most of the value. If you replaced the middleman celebrity with a virtual celebrity, McFedries imagined, you could distribute value to the people on the edges. By 2016, he knew the technology to create a believable, relatable avatar like Lil’ Miquela existed, and he sensed that consumers would be willing to interact with her. From the manufactured stars of his childhood—he cites the cartoons Alvin and the Chipmunks and Jem and the Holograms, and the human duo Milli Vanilli—McFedries saw that people could love an illustration or a band with a fake backstory. And now that interactions with “real” celebrities were almost exclusively through phone screens—perfect for an avatar—he saw that technology and consumer psychology had converged.

The second innovation was a new kind of process. McFedries was into cryptocurrency by 2013 and felt like its ability to assign value to new kinds of products, services and transactions made it uniquely suited for his ultimate goal: To distribute wealth to people on the edges. He figured the how of it all would be worked out as he went, but McFedries had a vision for digital goods running on a blockchain that could allow this virtual celebrity, or any piece of creative work, to be made by a collective working collaboratively as part of an organization across platforms and benefiting directly from the content’s sales or licensing. McFedries’ vision was more opportunity and wealth for the armies of creatives who currently make a fraction of the wealth that a movie, album, TV show or celebrity generates. “I’m really concerned with building better futures for innovators and creative people,” McFedries says. He bet that those improved futures would be built atop virtual economies. He felt that the economies themselves were inevitable—digital tokens were already being accepted as money—and became obsessed with making sure these new economies would not incentivize the same dynamics of traditional economies. He wanted to shift value to the edges of creative communities, even if he wasn’t yet totally sure how that would happen. “There are so many talented people that don’t have a shot,” McFedries says, “so I think about it every day.” Zhan could see the trajectory from Lil’ Miquela to Marvel, but more so, she said she trusted McFedries to create something that could appeal to many.

And she was right to. Today, Lil’ Miquela, who McFedries created alone before joining with collaborator Sara Decou, has 3 million Instagram followers. She is repped by the Hollywood agency CAA, appearing as a CGI avatar in a Calvin Klein video kissing Bella Hadid, modeling for Prada on her Instagram, and releasing singles on Spotify with millions of streams. Sequoia came in as an early investor, backing Brud in 2018, the same year Lil’ Miquela was named one of Time magazine’s most influential people on the internet. By 2021, Brud was valued at $125 million before it was acquired by blockchain game designers Dapper Labs. Today, Lil’ Miquela is one of many avatars creating a new ecosystem of content. But for McFedries, she was his first crucial step toward the new creative economy that he’s building now.

As a skateboarding, X-Men-loving Black kid growing up in Davenport, Iowa, McFedries said he was both a “techno-optimist” and “socio-anarchist.” Davenport is a port town on the Mississippi River; McFedries’ grandfather drove a tugboat and his other grandparents were auctioneers. His mother had tried to make it in Los Angeles as a model and actress, but after McFedries was born, she and his dad split up and she returned home to the Midwest with her 1-year-old. A single mom, she worked in factories for years before studying nursing at community college and later working as a nurse. McFedries remembers how Davenport was so completely defined by its economy—even down to its smell. “Often at night in the summer, you would just smell rotting pigs in the sewers,” he remembers, a result of runoff from the Oscar Mayer plant. That was oddly coupled with the pleasant, familiar smell of the Wonder Bread factory that he would pick up on cross-town drives.

McFedries loved Davenport. He started coding as a hobby and helped his grandparents auction items on eBay, but he had to go to Iowa City to find his scene at a record store. He knew the world was so much bigger outside Davenport, and he wanted to be part of it. Through pop culture—the movie “Hackers,” the WIRED writing of Kevin Kelly—McFedries immersed himself in the nascent internet culture of the ’90s: information wanted to be free, technology could change the world for the better. He was also drawn to more anti-capitalist ideas, listening to a lot of Rage Against the Machine and hardcore punk. He was listening to bands that emphasized overthrowing systems and empowering the poor, “literally eco-terrorists were like playing punk rock about tearing it all down,” he says. Then, in 2002, in the middle of high school, his mother suggested he move to Los Angeles to live with his father. He was a talented athlete, and she said he’d have more opportunities to play sports in college if he moved to a big city. “It was always clear that Davenport wasn’t the center of what’s happening,” says McFedries. “I think I wanted to participate in that center, but I think the only vehicle for me to understand how to do that as a young person was through athletics.” So, at 16, he started making friends and playing football at Beverly Hills High School.

His new friends invited him to their homes, and suddenly he found himself sitting on the couches of the West Coast elite. Some of his friends’ parents were helming massive companies shaping American fashion and culture. He says at first, “there was still this kind of idea that these titans of industry surely must have a skill set that you didn’t.” But, listening to them tell stories, McFedries realized the key to getting paid to be creative was capital, not skills. He saw that they already had money to cushion them by the time they took creative risks. “And so I was like, okay, I need capital,” he says, “and I need the opportunity to take those kinds of risks. I feel like I’m as capable as they are.”

After high school, he received a football scholarship to San José State and began studying software engineering, but he dropped out to move back to Los Angeles and build a reputation—social capital— that he could leverage for actual capital. Like many L.A. strivers before him, McFedries wanted to be seen as a man who had vision, who could forecast a trend or choose the right music or art before, or better than, anyone else. And he could. He DJed Katy Perry concerts and the entire 2008 Warped Tour. That same year he put out a top 10 album as a member of the group Shwayze. He worked in A&R for Photo Finish Records and directed music videos for Steve Aoki and NERVO. He hosted an iHeartRadio show for Dim Mak Records and became a spokesman for VitaminWater. He worked with singers BANKS and Ke$ha. He was an artist advocate at Spotify and an entrepreneur-in-residence at Bad Robot. As McFedries closed in on 30, he decided he’d generated enough social capital to start trading on it. At the same time, he’d developed a new understanding of celebrity.

Get the best stories from the Sequoia community.

Celebrities are “a team sport,” he says, but only players connected to the biggest names win. The limited opportunity for financial success in creative industries broadly disincentivizes people from joining creative fields, McFedries says. If only a tiny segment of poets, artists or fashion designers can make a living, why try? Why create, especially without a cushion of capital to fall back on? McFedries says flourishing in a creative field is about where you live, and who you know. McFedries can name friends who might’ve been great art directors but, without a path to opportunity, they ended up hanging drywall in Iowa. He can think of bands that might’ve been on par with Red Hot Chili Peppers, but without the social capital of Southern California to propel them, they stalled in Davenport. McFedries doesn’t just see this as a problem for artists; he sees it as a problem for American culture writ large.

“This idea of capitalizing on talent, this idea that, as a nation, we should be identifying people who are talented and maximizing their skillset, obviously is one that we fall short of where we should be in the United States.” Without incentives to create, “there are no new ideas,” he says, no new stories from new kinds of people with new perspectives. Instead, old ideas are repackaged, retold and resold by those who own the rights, with the same traditional narratives and limited cast of characters. “All I’m thinking about all day is how to create better incentives for creative people,” McFedries says.

“Rihanna or Ariana Grande, or whoever they are,” he explains, are “effectively the vehicles for a lot of creative people, whether it’s choreographers or songwriters or producers.” He figured if you could create a digital vehicle, and have it collectively owned by its creators, “there actually would be more margin for creative people and for the business itself.” He envisioned a future of virtual stars who speak any language, with stories and styles built not around the tastes of a few industry executives, but curated by countless creative people, all with a financial and artistic stake in the virtual celebrity. “You could create these celebrities that could create a ton of value,” McFedries says. So he founded Brud in 2014 to prove that avatars could connect with fans and drive value for collaborators.

“Rihanna or Ariana Grande or whoever are effectively the vehicles for a lot of creative people, whether it’s choreographers or songwriters or producers.”

TREVOR MCFEDRIES

And it worked. By April 2018, Lil’ Miquela had almost a million followers, enough to beget brand sponsorships and account monetization. She’d shown that, unlike one celebrity who only needs so many makeup artists or choreographers, Lil’ Miquela could do endless work on any number of platforms, creating exponential opportunities for people to work on projects featuring her. McFedries started to expand his team, and in 2018, he invited Nicole de Ayora on board as director of operations. The two bonded over having grown up in small towns and how that shaped their understanding of the internet. “We both really relied on the internet as a way of connecting with people outside of our small communities,” says Nicole. “It was a way of escaping a lot of what we were experiencing at a young age.” She was eager to join McFedries and his small team, now working to grow Lil’ Miquela so the avatar could do more than work with brands and post compelling selfies. The team at Brud wanted her to be able to tell meaningful stories to more people around the world.

Brud filled its offices with photographers, writers and CGI artists, and Lil’ Miquela’s online identity grew more elaborate, with new friends and more complex stories. At the same time, she was bumping up against the limits of her world—the platforms on which she was interacting with her fans. The influence of algorithms was becoming more obvious to consumers, hemming in people’s experiences by choosing what they would see, as opposed to people just seeing what popped up in a chronological timeline, or via their own curiosities. McFedries saw this as creating distance between creators and fans. The platforms themselves were increasingly seen as the new economy’s new middlemen, shilling ads, collecting data and soaking up profits. There was pushback against these practices, in the form of laws focused on protecting consumers’ data. In 2018 the General Data Protection Regulation law went into effect in the E.U. and in 2020 California followed suit with its own Consumer Privacy Act. McFedries and de Ayora were looking for a solution that let fans connect and participate more directly. They imagined a future where contributors and fans owned Lil’ Miquela and her projects outright, as a collective, where a limitless amount of creative work could be done across the world, simultaneously and collaboratively. He needed an online cooperative system, not a company, one that could serve thousands of people making all kinds of contributions.

He knew there was a work model for this, a Decentralized Autonomous Organization or DAO. A DAO is a collective that uses cryptocurrency tokens to vote on how to run itself, from putting value on anything created or contributed, to deciding how any profits are distributed. Today, there are thousands of DAOs, some controlling up to billions of dollars in assets, focused on topics including sports gaming, cryptocurrency and governance. The DAOs could solve these collaboration and ownership needs. But as he’s wont to do, McFedries had an even bigger idea. He wanted to enable people to be paid for work typically seen as intangible or non-monetizable. He wanted people to get paid for things like being fun at a party, offering a suggestion on a photo shoot or encouraging a friend with a smart insight.

To bring these ideas together and test them, McFedries co-founded the Friends With Benefits DAO in 2020. He wanted to see if, by inviting the right people to make the right vibes and creative projects, many more people than the DAO could accommodate would want to join, thus driving up the value of the tokens and giving those vibes a tangible worth. “Having a point of view is hard to measure,” says McFedries, “and should be valued. And we should create economic systems that value those things, because otherwise, we’re just perpetuating the same structures of the past.” McFedries has compared a DAO to a Facebook community where the people posting content, those responsible for making the platform interesting and attractive to more people, also share in the value those posts create—rather than that value accruing to a central corporate entity.

To flourish financially, the DAO must flourish creatively. McFedries knows creative work is most likely to surface in spaces where people have real relationships and feel supported to try new things. He is working to foster trust and engagement by setting up community principles, organizing people around potential creative projects, with chapters in London, New York and Los Angeles. Today Friends With Benefits has a waitlist and about 6,000 active members, including musicians Erykah Badu and Azealia Banks, as well as lawyers and software engineers. So far, they’ve collaborated to make real-world art and digital art in the form of NFTs. They’ve started a fellowship program for creatives from underrepresented communities, which will offset the entrance free of more than $3,000, and they’re discussing launching a beverage businesses, writing essays on the history of decentralized “benevolent anarchic” organizations (like Alcoholics Anonymous) and forming friendships, all value that McFedries says is being captured in the DAO’s token.

But even as Friends With Benefits proves his value-to-vibes idea, building new things is always going to get messy, McFedries admits. In 2021, the service that hosted the Friends With Benefits cryptocurrency token was hacked and the token lost 99 percent of its value, essentially making the collective worthless. But the members regrouped, issued a new token and today its price is $11.80, down from a high of just over $186. That, coupled with how Friends With Benefits has been labeled “the digital Soho House,” means it’s under pressure to live up to the hype. If it doesn’t create notable work, or it’s not fun, the tokens will lose their worth and the DAO becomes just another Discord chat with some meetups. But living near this edge, where value is being assigned to new things in new ways, some of which are still being tested, doesn’t faze McFedries. After reading “Debt: The First 5,000 Years of Money” by the late anarchist anthropologist David Graeber, he found himself asking, “like what the fuck is value?” and he followed that destabilizing thought to a liberating conclusion: It’s whatever we collectively decide it is. “One of the reasons that I love crypto, or an internet of value, is that we have really antiquated vehicles for representing value,” he says. He believes crypto enables better instruments for assigning value to all things.

“One of the reasons that I love crypto, or an internet of value, is that we have really antiquated vehicles for representing value.”

TREVOR MCFEDRIES

Web3 proponents are sometimes dismissed as wanting to decentralize the web just enough to get some of the power that corporations and celebrities now have for themselves. For example, some people dismiss Lil’ Miquela as just another spokesmodel, and Brud as manipulative of her fans. But with Dapper Labs’ purchase of Brud, McFedries has a mandate to figure this out and help build the tools and habits to make DAOs mainstream enough to realize their promise. He’s the CEO of the new Dapper Collectives. A near-term order of business is handing Lil’ Miquela over to her fans. McFedries and his team are turning Brud the company into Brud the DAO, which he says is scheduled to open to the public at the end of August. Lil’ Miquela will be at its center. Brud will ask members to help write her storylines and contribute to her computer-generated design and 3D artwork. Fans, now collective members, will receive writing and design credits tracked through on-chain resumes. There will be incentives for DAO members to share content to be sold, and then all token-holders will get a cut. As de Ayora, now CPO of Dapper Collectives, puts it, “At the end of the day, we created Lil’ Miquela but they gave her value and meaning.”

For the next while, McFedries cautions, things will look much as they do now, with platforms like TikTok or Instagram capturing a lot of the value of the DAO’s creative work. But if DAOs and other components of Web3 take off, “there will be virtual goods and economies that would be bigger than (people) could ever dream of…we’re starting to cross that chasm now.”

All of this is taking McFedries, and maybe the rest of us, toward his biggest goals: sustainable financial futures for creative people and connecting everyday people, like the ones he grew up with in Davenport, with the kinds of opportunity he saw when he moved to Beverly Hills. “If you can…reach out across the divide, and give them the opportunities and the language…, we can have this improved capitalization of talent,” he says.

There are success stories in these new budding economies: an FWB artist went from being broke to buying a house during the pandemic. A writer sold an NFT of his essay for about $150,000. Outside FWB, artists have found that DAOs have kept them in the creative game longer than they’d imagined possible. McFedries knows this is just the start of something, a potential alternative to the systems that he sees countless people trapped in. He also knows it’s an urgently needed alternative. He thinks constantly about all the people who never earn the real value of the work they do. All the people who can’t afford to take the big risks his high school friends’ parents did, or who never left Davenport and instead watched its factories close. He knows he got lucky when he moved to L.A., to the center of a scene he fit into and shaped—and that most people never get that chance. Ask him how often he’s hit with the realization that his friends back in Davenport might’ve been just as successful as the creators he knows in L.A. and he doesn’t hesitate: “It really happens every day,” he says. “And that’s why I want to make big things.”