DoorDash ft. Tony Xu – The “Wrong” Moves That Built a Giant

DoorDash faced skeptics from Day 1. Grubhub, Delivery.com, and others were already addressing the restaurant delivery market when CEO Tony Xu and his co-founders started in 2013. But after talking to hundreds of local small businesses, they realized there was still an unmet need: None of the competitors solved the problem of delivery with an on-demand workforce, the way Uber had done with drivers. After struggling to raise initial funding, DoorDash found traction. But the next few years would prove tumultuous, with cash scarcity and investor skepticism putting the company perilously close to the brink. The founders’ contrarian decisions, clarity on their commitment to serve small local businesses, and ability to out-operate competitors has turned DoorDash into one the decade’s biggest startup success stories.

Listen Now

Key Lessons

DoorDash co-founder and CEO Tony Xu led the company from a Stanford GSB project to the global leader in on-demand delivery, navigating intense competition, financial struggles, and pandemic-era disruption on the way. DoorDash’s journey offers valuable lessons for founders:

▶ First-principles reasoning lets you have conviction in contrarian strategies. DoorDash focused on suburban markets rather than densely populated cities, recognizing the greater need for delivery in areas where restaurants weren’t within walking distance. This flew in the face of conventional wisdom, and helped them gain a foothold against established competitors.

▶ Clarity in your vision helps you endure in the face of skepticism. Despite rejection from many investors who viewed food delivery as unsustainable, Tony and his co-founders remained committed to their long-term vision of becoming the “FedEx of local delivery.” This unwavering belief carried them through difficult times.

▶ Clarity in your values helps you make bold decisions in the face of uncertainty. During the pandemic, DoorDash cut commissions for restaurants by 50%—a $100 million revenue hit—and advertised competitors in national campaigns. These moves strengthened relationships with merchants and consumers, ultimately benefiting the business.

▶ Focus relentlessly on unit economics and operational efficiency. DoorDash’s ability to acquire customers more efficiently than competitors gave them an edge even when facing better-funded rivals. Their maniacal focus on improving delivery times and eliminating defects helped drive profitability.

▶ Build a culture of resilience and shared values. The challenges DoorDash faced in its early years—including multiple difficult fundraising rounds—forged a strong team culture centered on frugality, customer obsession, and perseverance. This foundation was crucial to their later success.

▶ Balance short-term pain with long-term gain. Many of DoorDash’s most impactful decisions involved significant short-term costs or risks. The willingness to make these tradeoffs—like taking on heavy dilution to secure a large war chest of financing—enabled their rapid growth and ultimate market leadership.

Inside the Episode

The People

Transcript

Chapters

- Introduction

- From Stanford GSB to Small Business Solution

- DoorDash’s First Crisis and the Birth of Customer Obsession

- Standing Out In a Crowded Market

- A Contrarian Strategy: Focus on the Suburbs

- Navigating Challenging Fundraising Decisions

- Navigating the Pandemic

- Expanding to Europe via Wolt Acquisition

- Lessons From the Journey

Tony Xu: Besides just the constant financial stress, we had people lose confidence in the company, right? Even internally—about maybe a quarter or 20 to 25% of the company—voluntarily left over those three years.

We were presented with an opportunity to take a large war chest. I thought, “Look, it’s not a guarantee, but we get to put aside any concerns of ever having to raise capital again, and we get to just step on the gas and take what we already know is the best product and just bring it everywhere.”

Introduction

Roelof Botha: Welcome to Crucible Moments, a podcast about the critical crossroads and inflection points that shaped some of the world’s most remarkable companies. I’m your host and the Managing Partner of Sequoia Capital, Roelof Botha.

DoorDash is synonymous with delivery, but this was far from inevitable. Founded in 2013 as a category underdog, today DoorDash operates in over 30 countries, with nearly $10 billion in annual revenue. It has transformed into the global leader in on-demand delivery, expanding to groceries, household items, pet food and much more.

In today’s episode, we’ll look at how DoorDash broke into the competitive restaurant delivery category with a non-consensus strategy, how they survived three years of cash scarcity that nearly put them out of business and how difficult decisions made during the pandemic helped propel them to category leadership on a global scale.

From Stanford GSB to Small Business Solution

Tony Xu: It was the fall of 2012, and actually, the premise that got all of us together was really, “How do we help small businesses?”

My name is Tony Xu. I’m the founder and CEO of DoorDash.

Roelof Botha: DoorDash’s journey began at Stanford University. Founders Tony Xu, Stanley Tang, Andy Fang and Evan Moore met in an entrepreneurship class at the Stanford Graduate School of Business called Startup Garage. The foursome decided to partner on a class project.

Tony Xu: All of us have our own stories in terms of why we have an affinity towards small businesses. Mine happens to be personal in that I have a connection to a small business that my mom ran. I grew up in Illinois, and one of the ways in which I hung out with my mom as a child was actually working alongside her inside of a Chinese restaurant where she worked in Champaign. And so, I’ve always had an affinity towards, how do you help these underdogs who don’t really view their businesses as a profession; they view it really as a lifestyle. How do you help them be successful?

The idea for DoorDash actually didn’t come right away. We spoke with three or four hundred small businesses across pretty much every category—retail, restaurants, services. And the main question we asked them was, “Tell us about all of the activities that you do every day.” I think it was a lot easier to see a specific problem in plain sight than to try our best to interpret a generic answer of what might be a challenge for them.

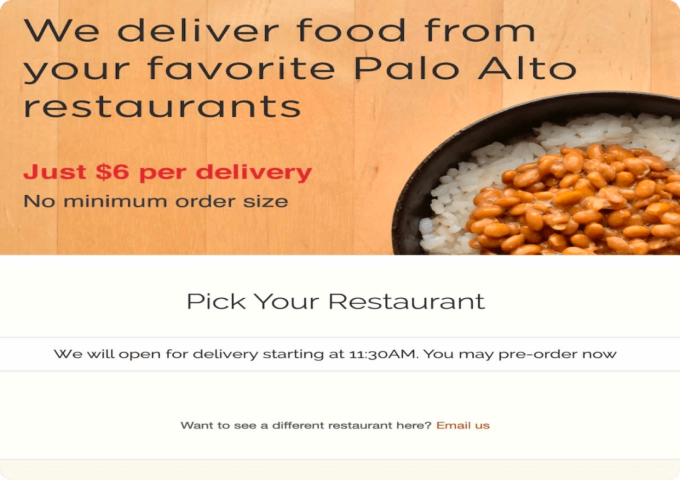

And so, one of the small business owners, her name was Chloe, ran a macaroon store in Palo Alto. She was a one-person shop. She showed us a booklet of delivery orders that she had refused. Small businesses don’t have the luxury of turning away business. I would say most people don’t have the luxury of turning away business, but for small businesses who, on average, have 17 to 18 days of cash, you really have no luxury to be able to turn away business.

And so, Chloe was turning away dozens of orders per week, which was very strange. And so, when we talked to her about it, she let us know that they all happened to be delivery orders. And as a one-person operation, there was no way that she could fulfill those orders. And it just occurred to us that it was 2012-2013, and it was surprising that she would have to do this on her own. Delivery is not a new concept—it’s probably been around for hundreds of years. Yet, in 2012-2013, the vast majority of restaurants, and certainly the vast majority of retailers, did not offer delivery.

Alfred Lin: Prior to DoorDash, there were restaurants that delivered on their own. You would get menus from them, they would be placed in the kitchen, or you would put them on a magnet on your fridge and you would call all the different restaurants individually to order food. And that was generally the way you ordered delivery.

I’m Alfred Lin. I am a partner at Sequoia Capital.

There was a company called Grubhub and another called Seamless, and they became an order-taking platform for some of those restaurants. And so, they took the order on the web, and then they routed it to the restaurant, and the restaurant still fulfilled the order by making the food and then by delivering it. While that was a better experience, it was just so limited to the restaurants that would be willing to do their own delivery. DoorDash recognized that restaurants wanted to offer delivery, but they couldn’t afford the delivery staff.

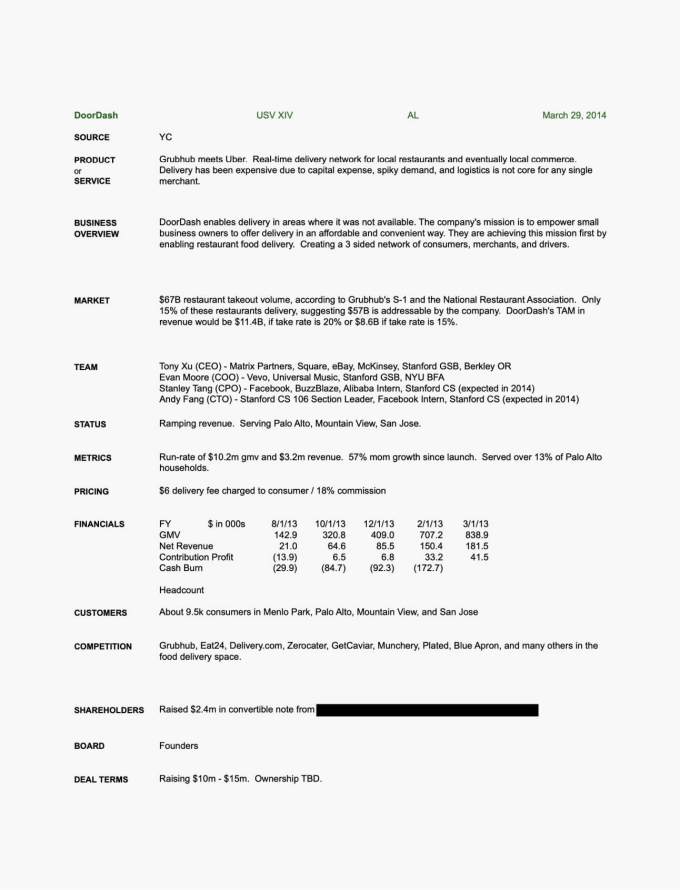

Roelof Botha: The founders were accepted to Y Combinator in the summer of 2013. Their pitch was food delivery for every restaurant, delivered to customers in under 45 minutes. They also had a larger vision: to one day become the FedEx of local, delivering not just food, but any item to people’s doors.

But on Demo Day, when DoorDash presented to a room of investors, most were skeptical.

Alfred Lin: We decided to pass on the seed because we weren’t sure whether DoorDash would be a mainstream service or whether it was only a service for college students financed by their parents.

Tony Xu: Yeah, DoorDash was not the fan favorite at the YC Demo Day for the summer 2013 batch. I think there were a lot of skeptics around whether or not delivery, in and of itself, would ever be economical or sustainable as an activity, let alone a business. I think there were a lot of questions about possible competitive dynamics heading into the future. And DoorDash, given the fact that the four founders were first-time founders with only 12 weeks of demonstrable traction, didn’t really have that much to sway investors in an overwhelming way to be a fan favorite. And so, we were probably bottom half in the batch.

I think what was most important for the four of us at the time, and certainly what got us through any initial bouts of rejection, was the fact that we really enjoyed working together. And we felt, first and foremost, we owed it to ourselves to answer the question: Is this worth our time? Is this a product that customers will be willing to pay for? Would restaurateurs be willing to partner with us and pay us a commission for that partnership and incremental business? And finally, you know, the Dashers—the drivers on our network—would we be able to partner with them and actually afford payment that they would find attractive?

And so, those were the questions that really we were pretty maniacally focused on answering.

DoorDash’s First Crisis and the Birth of Customer Obsession

Roelof Botha: Despite initial rejection from investors, the founders refused to give up.

Tony Xu: Our first crisis as a company came in September of 2013. It was the first home football game at Stanford, and we had very little money—I mean, days, maybe a couple of weeks of runway left in terms of our cash balance.

And the football game had the effect of just giving DoorDash a lot of orders. Now, a lot at the time was like a hundred orders or something like that, and it was certainly a volume that we were not prepared to handle. I remember pretty much anything that could have gone wrong went wrong. Every single order was late, probably by an average of at least 45 minutes; some orders were as late as over an hour. It was one of the worst days certainly in the first hundred days of the company’s life.

At the time, everyone at the company, we’re the only ones doing deliveries. And so, we fulfilled all the orders. And it was late into the evening, and the founders came together and said, “Look, if we wanted to do what’s right by customers, the refund would cost something north of 40 percent of our bank account.” And when you have days of runway, that decision seems a bit more consequential. It took us maybe 15 seconds to hit the refund button. And on top of that, we actually stayed up all night and baked cookies that we all delivered before 5 a.m., before the customers who we wronged would wake up and hopefully make right by them.

To us, we had a vision of what high standards were. We’d rather die trying to achieve excellence than live to be mediocre. I’m very proud that, you know, that story became the centerpiece of what inspired the company value of being customer-obsessed, not competitor-focused.

Standing Out In a Crowded Market

Alfred Lin: There are many things that stood out about Tony, and Stanley and Andy. They were outliers—they were a group of people that had very sharp insights into the restaurant industry. And in particular, Tony had an incredible amount of founder-market fit for this business. You know, we passed on the seed, but there was just a level of effervescence about Tony that I really liked. And so, I continued to follow him for a period of time.

And we met with him multiple times, but the one meeting that I remember most was sitting down with him at dinner at a Chinese restaurant—I believe it was Chef Chu’s in Palo Alto. In this dinner conversation, I sort of was able to see this. He thought about things at a very high strategic level and then would break down an idea or a problem down into smaller and smaller and smaller problems, or smaller and smaller ideas that you could go execute on. While he didn’t use the word at the dinner “operating at the lowest level of detail,” that’s what he was doing when he and I were talking at that dinner. And that was just very impressive to me that he could take a high-level idea or problem and break it all the way down to its lowest levels, and just iterate that again and again and again.

Right after that dinner that I talked about, I immediately brought them in. They had also been meeting with other firms, and their Series A was just easier to raise partly because the business was growing—and it was growing nicely. I’m not sure it was easy for me to convince my partners, but I think they got tired of me speaking about how I grew up in New York City. In New York City, restaurants delivered, grocery stores delivered, dry cleaners delivered and why was the rest of the country so backwards? A service like DoorDash should exist for the rest of the country. I think I just wore my partners down.

Roelof Botha: In May 2014, Sequoia led DoorDash’s Series A financing.

Tony Xu: You know, for the four of us, when we were starting DoorDash, we always had the same vision, which was to build this last mile FedEx—or the “FedEx of locals,” is what I believe I pitched over 10 years ago at this point. And while that vision has always remained the same, it wasn’t obvious exactly how we’d get there.

Roelof Botha: Food delivery is a notoriously difficult business. On top of providing an experience where food arrives on time and at the right temperature, margins are razor thin.

For a food delivery service to succeed, it needs enormous order volume. Because profitability requires such scale, the category can only sustain a few winners.

DoorDash faced an early crucible moment: how to break into the delivery category and differentiate itself from competitors, which by this point included Postmates, Caviar and more. Tony and his co-founders needed to develop a strategy for quickly gaining market share and finding product-market fit.

A Contrarian Strategy: Focus on the Suburbs

Tony Xu: For companies just getting started, how you set them up does matter. If you get it right, doubling down can carry you really, really far. And if you get it wrong, it can be really painful and take a really long time to fix.

And in the earliest days, we were pretty clear-eyed in the sense that the most important thing was to find product-market fit. And from a business perspective, you know, in terms of making deliveries sustainable and economic, you need high density. To get high density, you need to go to a place like New York City, but this missed, in my opinion, completely the perspective from the customer. You know, in New York City, we can just walk down the stairs or take the elevator down and get whatever we want within minutes. However, that’s not true anywhere outside of the city center.

And so, to me, if there were ever a place to create a company from scratch or create a category from scratch, it would be outside of the city centers.

Alfred Lin: I was initially somewhat skeptical about the suburb strategy. This was not obvious—everyone else focused on large cities, believing if you won the cities, you could have a decent business.

Tony Xu: Look, I mean, a lot of times conventional wisdom is called conventional wisdom because it’s correct. And we had studied, actually, the case studies of many companies that had come before us—you know, Webvan, Cosmo, lots of great companies who tried really hard to make similar ideas work in a previous era. And it is interesting. Virtually all of them started in city centers, and, you know, that made sense in terms of where deliveries were happening naturally. It happened in city centers.

And so, the idea to go outside of the city center we recognized was not the most popular idea, yet from what we had heard from customers in a place like Palo Alto, where we started the company, or San Jose, where you’d have to drive to pretty much get anything, that person would tell us, over and again, how much of a time saver—and some would even use the word life saver—we were. It just kept on repeating itself as the number one thing to focus on.

Alfred Lin: They sort of walked me through their logic: everybody was going into the cities, and every order was not profitable because there’s so much competition in the cities. And this insight that it was less competitive in the suburbs, and we could make more money in the suburbs, it’s more valuable for your food to be delivered to you because it’s not down the street, was in and of itself compelling. It’s like, yeah, that’s right—I have to actually get out of my house, get in the car, drive a fair distance, go pick up the food and bring it back. So that insight was point number one: from a consumer experience, it’s actually more valuable for a consumer in the suburbs to have their food delivered to them.

Then the second insight that Tony had which is in almost all small towns, there is a main street. And I was like, “Really? Huh.” And at Stanford, off of Stanford, there’s University Avenue, where all the restaurants were. In Palo Alto, there’s California Street. And so, then I sort of went and checked a bunch of other places—small towns and small cities—and it’s true that many of the restaurants were consolidated. They were aggregation points, they were starting points for where you can radiate out. And that just made the problem of logistics a bit easier than you would have thought if you thought restaurants were randomly dispersed throughout a small town and a small city.

So with those facts, I was convinced. Then over the years, with the data they showed on their ability to make the suburbs more profitable and faster, that was very convincing, time and time again.

Tony Xu: As the entrepreneur, you certainly need conviction, but you also need evidence along the way to make sure that you’re not delusional. I think we always saw the evidence as we rolled out cities number two, three, four, five, etc. You know, the same types of behavior and the same types of responses from customers, and merchants and Dashers that gave us the conviction that we can repeat this across all parts of the U.S.

Alfred Lin: In general, I would say DoorDash has always been very good at making the right but non-obvious decisions, and there are lots of examples. Suburbs is one of them. They have a three-sided marketplace: consumer, Dashers and merchants. And they chose to be merchant-first, which was very clarifying and it’s very focusing for the company, but it’s not necessarily what most companies will pick. They would probably have picked consumer-first, and their focus on merchants was why they were able to win merchants over, which was then their ability to then provide mass selection for the customer.

And so, instead of having just a few restaurants in a neighborhood, you’ve got all the restaurants in the neighborhood. If you had the whole neighborhood’s restaurants, I’d go to DoorDash.

The other thing they focused on was this concept of having an accurate delivery time estimate. And that seemed like, “Wait, why are you focused on that so much?” It turns out that getting that time estimate down is really, really important to setting customer expectations. The other non-obvious thing is when you get the delivery time accuracy right, you set the customer’s expectations, but it also allowed us to batch things in much better ways, which then lead to a much more efficient Dasher operations.

On the national chains, instead of just winning one or two, such as McDonald’s or Starbucks, they wanted to win over the top 100 national chains. That allowed them to stay true to who they are, which is about providing selection. And also, having all of them kind of pulled them nationally and made for a much more efficient expansion nationally, than going city by city.

Navigating Challenging Fundraising Decisions

Roelof Botha: By 2015, the company had hit 1 million deliveries and was operating in 22 U.S. markets. DoorDash was growing quickly. But growth necessitated rounds of financing—some of which would bring difficult lessons and test the company’s resilience.

Alfred Lin: The business continued to grow, and grow very, very quickly. Before they went out to raise their Series B in 2015, we tried to convince DoorDash to take an offer from Sequoia for $250 to $300 million. They didn’t really laugh at us, they did kind of chuckle at the price. And they would later go on to raise that round at a $600 million valuation from Kleiner Perkins.

Tony Xu: It just happened to be that the Series B was a very competitive round that came inbound to us, and we received multiple term sheets in half a week. And I think the competitive dynamics—that tends to be how some of these very high valuations come about.

Roelof Botha: Not everyone was excited about the lofty valuation.

Alfred Lin: I was just very concerned when a company’s valuation grows so quickly. And while I had belief in the company, I was very, very concerned that it would be very hard to clear the $600 million valuation at the next round. And I absolutely discussed those concerns with Tony, and he had a lot of confidence in the business then. And he believed that he could grow into that valuation.

Tony Xu: You know, it was a time where it seemed like DoorDash could do no wrong, and everything was moving up and to the right. But on the flip side, you know, momentum can shift really quickly.

Roelof Botha: Raising its Series A financing had been easy in 2014, as was the Series B in 2015. But when DoorDash went out to raise its Series C in the first quarter of 2016, the sentiment had changed.

Tony Xu: Within a matter of two or three weeks, everything went from “Oh yeah, this will be a fairly straightforward financing to continue the company’s expansion plans” to “The industry is toxic,” and the start of three very, very difficult years with the company.

Alfred Lin: We just got no after no after no. I think some people called food delivery a cash incinerator.

Tony Xu: We were not yet profitable. I remember the investor perception that, you know, there was no way you could ever make money doing last-mile delivery. You can grow very quickly, but there’s no way you can do it sustainably, and those became very powerful forces.

Alfred Lin: When we look at financials, we want to see lots of revenue in black and lots of profits in green on the bottom line. DoorDash’s financials were not that much revenue in black, but a huge amount of losses in red on the bottom.

Tony Xu: Companies like DoorDash are what I call minimum-efficient scale businesses where up to a certain point of scale, you’re not making money. You’re investing in the growth of that geography or that product line, and if you know how to do that very successfully and build the highest quality product with the highest, you know, retention and frequency, then you can keep investing. And if you can, in parallel, improve your unit economics, at some point of scale, the numbers turn to the other side very quickly. But it does take some amount of patience to get there, and it does take some amount of capital to get there. And even though we always had the formula, investor patience during that 2016–17 era was fairly thin for companies like ours.

Roelof Botha: Struggling to raise money, DoorDash faced a cash crunch.

Tony Xu: I always was nervous, and I think a lot of people involved with DoorDash were very nervous about, you know, our solvency. We were always worried about running out of cash and it was three years of being worried.

Roelof Botha: After dozens of rejections, Alfred approached the Sequoia team to make the case that we should lead the round.

Alfred Lin: The Series C was hard for DoorDash because they were going to run out of money. It was also hard for Sequoia. It was hard for me, and it didn’t really matter how much we loved Tony or how much we believed in the market. We needed to prove ourselves mathematically, in spreadsheets, that this could be a good business, and it was not that easy to do.

It took three memos to convince the partnership to lead the Series C. The data that was positive was the customer retention, and the cohorts of the retention was really strong. When you break down the retention, you could see a set of customers that kept ordering more and more and more. They were the power users, and the power user group was growing. And then the order baskets kept growing for those customers. And so, maybe the first order wasn’t profitable, but maybe the second, or the third, or the fourth and all the orders after, they were all profitable.

It was a very stressful time for me, Michael Williamson and Matt Huang, who were working on the three memos that got us to a decision to make the investment because we just didn’t take no for an answer. It was strained inside partnership conversations because there were partners who didn’t believe we should do this investment. We had to slowly answer all of their questions.

Their questions were all valid, and the best part about Sequoia is we make investments as a team, but we also always keep an open mind. And so, when we were able to answer all the questions, we were all on board to make the investment and we made the investment as a team. And then we said, “Okay, it’s all hands on deck to make sure that DoorDash becomes a winning company over time.”

Roelof Botha: DoorDash’s Series C financing closed in March 2016, securing desperately needed resources. But the round came at a cost.

Alfred Lin: The headline valuation was slightly above its last round, but the cap table that we received didn’t account for the option pool. We had agreed on a headline price, and then when we did the math for per share price, it was a 5% lower per share price than the previous round. There was a lot of swirl around the Series C being a down round, even though the headline price was slightly higher. And Tony had to go deal with that with the employees.

Forget about the slight down round of 5%—why are we even taking a flat round if the business continues to grow? And I often tell founders, your traction does not mean an equivalent traction in valuation, especially since you knew that you needed to grow into a prior valuation that you took at the Series B. But we got the round together, and that seemed like it was a good outcome for the company.

There was this notion at the time—I forget whoever said it—but there was a thought that the Series C would be the last round we would raise. And of course, when you go through that kind of an experience, why would you want to raise money again?

Roelof Botha: But the company did raise money again. This time, it wasn’t just to keep the lights on; it was with a specific goal in mind.

Alfred Lin: The tide was turning. There was always going to be a large amount of competition, and one company would be the leader. In this business, because you need so much scale, you need there to be one to three players at most. DoorDash was growing and growing fast, and so was Grubhub and so was Uber Eats. Uber Eats was growing very, very quickly, and winning against Uber Eats was not easy because Uber had a lot of cash and you were fighting against someone that had a lot more cash than you.

As much as DoorDash raised, it was tiny, tiny compared to the war chest that Uber had and their ability to direct that at the Uber Eats business. So, they started thinking about raising a Series D to try to win the market.

These guys have nerves of steel.

Keith Yandell: I remember my first day—we had a dashboard, and I logged on and I think we did 19,035 deliveries. And coming from Uber, I thought that it must be broken like they forgot a zero or two on the dashboard because we were small. We were growing really fast. It was exciting, but it was just a different universe than I had been at before.

My name is Keith Yandell and I am the Chief Business Officer at DoorDash.

I was working at Uber at the time as a lawyer, and a friend of mine had told me about DoorDash and thought it might be a good fit for me, both given my experience and because of the culture. I’m motivated by wanting to have an impact and we were definitely the up-and-comer. Grubhub was maybe eight times our size. Uber was well-capitalized and moving quickly. Postmates was about our size, maybe a little bigger than us. And then Caviar was out there. So it was a hyper-competitive marketplace.

So when I joined, we had just raised our Series C. We had adequate capital, but not indefinitely. We went out to raise the Series D starting in Q4 of 2016. The business was doing well. The cohorts looked good, and if you rolled those forward, you could definitely see a path to profitability—or so I thought. But it was a very, very difficult fundraise.

Tony Xu: Yeah, I think the Series D in many ways was a continuation of the challenges we experienced in the Series C.

Keith Yandell: Six to nine months, we heard more “no’s” than I can count. Then we got a term sheet from SoftBank in mid ’17, and that was a very exciting thing. It was a welcome relief to get the term sheet. I think it was a pre-money valuation of maybe $850 million, which was a slight step up from the last round. And even though we thought we were worth a little bit more, we had kind of learned the lessons from the Series B before, and a little step up was okay. And so, that was a happy day to get that in the door.

Alfred Lin: But at the same time, SoftBank was working on another investment, much larger investment in a different company, and they were somewhat distracted. Eventually, we found out that the other company that they were working on was Uber. And there was real concern that SoftBank would not close until they get clarity on what their investment opportunity was going to be in Uber.

Keith Yandell: They were very clear with us that Uber was their priority, and they did not want to close our deal unless and until they had cleared the HSR process with Uber. And that process dragged on for many, many, many months.

The days we were waiting for the SoftBank funding to come through were probably my toughest days at the company. Was there a time I thought the company might not survive? Absolutely—almost every day from late ’17 to early ’18.

Tony Xu: It was a painful time. It was a constant period of stress of not knowing whether or not we could ever raise money.

Keith Yandell: Tony would call me almost every night at about 8 o’clock, and we’d kind of go through the options of what we could do to conserve money, or if there was anything we could do to try to make the round come together more quickly. We started making contingency plans that we hoped we’d never have to use, but recognizing that we were getting to the point where we were talking about weeks of runway rather than months or years.

We put together a plan for who we’d have to let go and what we would have to do, which was really to become a niche business. We were going to have to become a lot more like Caviar looked at the time—which was a high basket size, high-end restaurants, limited selection and a very niche user base was the backup plan that we hoped we would never have to go to because we didn’t think that was the winning formula.

Tony Xu: Besides just the constant financial stress, we had people lose confidence in the company, right? Even internally—about maybe a quarter or 20 to 25 percent of the company—voluntarily left over those three years.

Keith Yandell: The people that stayed shared a similar mindset. And it was people who liked to be the underdog, and they wanted to solve the hard problem. And that was another core value of ours that came out of this: “One team, one fight.” Because others were better funded or they were bigger than us, we had no innate advantage other than each other. And I looked around when we were solving those problems and there’s people I want to spend time with, and that’s still true today. And so, I think I even recognized it then that I’d rather be the underdog in this fight than a cog in the machine of a fight that seemed like I wouldn’t really have a significant impact in the war.

Companies usually take on the ethos of their founder, and Tony is a very frugal person. And we always had a very frugal approach. I think what shifted was a maniacal focus on the unit economics of the business. So we were hyper-focused on shaving every second off we could from the time it took to do deliveries. How do we make it more efficient? How do we eliminate defects that are a bad customer experience, but are also really expensive for us?

Before we were cash-strapped, people would come in and say “Well, do you want to focus on growth or do you want to focus on profitability?” And we quickly realized that if we were going to survive this time, we had to do both at the same time. Eventually, we just made it a core value. It says “and,” not “or.” You can’t pick or choose. We must grow, and we must become more profitable.

Roelof Botha: As the company worked to stay alive, Alfred decided to go out on a limb once again.

Alfred Lin: So since we didn’t close the Series D at the end of 2017 and it was now 2018, I decided to ask the partnership whether we would consider the Series D and lead it ourselves. And I thought I was going to get fired from Sequoia for going back again and again to propose that we lead the Series C. For the Series D, it’s like, “You’re going to come back and ask for more money when we just led the Series C, and you had told us that maybe the company would never have to raise again, and you want to invest this large round?” I thought I was going to get fired again.

But everybody was quite receptive because the business was growing, and doing well and all the metrics were working. So we decided that we would consider it. It was less than what Tony wanted—I think our number for the round was $190 million, not $250 million—but it was also more than what we thought the company needed.

Keith Yandell: We were waiting for the SoftBank money to come in, and we’re getting down to the felt, as they say in poker—like we were almost out of cash. Then Sequoia came in with a term sheet of its own. It was slightly less pre-money valuation than SoftBank was, and they said, “Let’s just take our money and let’s go forward and execute.”

And then SoftBank came back and said, “We’re ready to close.”

Roelof Botha: A twist. The offer from Softbank was back on the table.

Keith Yandell: And so, we had two term sheets from two partners we valued. SoftBank had been the first to show up but hadn’t closed. And Sequoia had backed us in every round and had really catalyzed the Series D coming together. And we didn’t want to take that much money, but they both really wanted us to pick them.

Roelof Botha: This was a crucible decision. The total amount on the table was $535 million. DoorDash needed to decide how much money to take and which partner to choose.

Keith Yandell: Tony and I were sitting in the lunchroom, and we had decided to take just the Sequoia check. And he didn’t look like he was feeling very well, and I said, “Tony, what’s going on?” And he says, “I can’t explain it, but this just doesn’t feel right, but I’m not sure what else to do.”

And Andy Fang, who was one of the other co-founders, came by and said, “Why don’t we just take both checks?”

At the time, it seemed outrageous because it was like half a billion dollars on a sub-billion-dollar pre-money valuation. The dilution would’ve been crazy.

Tony Xu: The company was going to take a lot of dilution. The founders also would have lost control of the board in terms of the number of seats that founders would have access to. It was one of these decisions where I knew it would be consequential.

I think ultimately, for me, it was thinking about what do we want to be true in 10-plus years. If I was just looking at this I think in a very short time period, perhaps we didn’t need to raise the quantum that we did in the Series D. But when I put things in perspective around—we believed we had the leading product, we had spent no money on marketing at the time, we had over three years of difficulty raising even a dollar.

When I put all of those things together on one side, and I compare it to the amount of dilution or cost of the capital that we would’ve incurred, as well as the loss of control on the board: Do I think that, you know, we could’ve created a company that’s worth 10 times the cost so-to-speak of what we gave up? And to me, it was conviction in that path. We were presented with an opportunity to take a large war chest. I mean, to me, this was just a moment in time where I thought, “Look, it’s not a guarantee, but we get to put aside any concerns of ever having to raise capital again, and we get to just step on the gas and take what we already know is the best product and just bring it everywhere.”

After raising the Series D, it was pretty obvious to me that the right thing to do was just to take our playbook everywhere. We went from launching maybe a dozen cities a month to launching 3,000 cities in six to nine months. It became this sprint where we felt like we had created the leading product in our category, and it was time to just bring it to all audiences and see how far we could take it.

Alfred Lin: The company knew its numbers and knew its competitors’ numbers down to a very, very fine level of detail. Tony was very comfortable raising a large amount of money, even though it was a small fraction of what Uber had, because he had a particular insight: that for every dollar that DoorDash spent on customer acquisition, they were able to acquire twice as many customers as their competitors. They were just a lot more efficient at acquiring customers.

Tony Xu: When you have that kind of advantage, it’s almost like saying you can run a four-minute mile when someone else is running a five-, six-, seven-, eight-minute mile. It’s just a matter of when you want to turn on the engines to actually blow by in the race, and that’s kind of, you know, how I felt we were set up. It was against the entire field, and so, once the money came, it was just go time.

Navigating the Pandemic

Roelof Botha: In 2019, DoorDash surpassed both Grubhub and Uber, becoming the U.S. category leader in food delivery. But as we all remember, early 2020 would bring new challenges.

Tony Xu: When March 2020 rolled around, it was not obvious whether or not the pandemic would be a massive headwind or a massive tailwind for DoorDash.

Keith Yandell: The pandemic was a time of great emotional twists and turns, ups and downs—high-variance environment. And I remember right when shelter-in-place happened, our volume fell absolutely off a cliff. And I thought we might go out of business because people weren’t sure how COVID was transmitted, and it might be transmitted through food. And so, you’re definitely not ordering online delivery if you’re worried about that, so our volume cratered.

And then, almost as quickly as it cratered, it doubled in a way that I don’t think we were fully prepared for.

Tony Xu: We doubled I think order volume in a week, I want to say somewhere towards the end of March, maybe.

Alfred Lin: When you go back in time and see the demand start increasing, you realize, “Wait, do I need to scale up for not a 50 or 100% increase, but now a 200 or 300% increase?”

What did we need to do? We needed site stability first and foremost.

Keith Yandell: The infrastructure is super sensitive to how many people are ordering at any given moment. The engineers had been building a business to scale quickly—I mean, we were doubling every year, doubling or more every year. So it wasn’t like it was a slow-growth business. But to double and then some, almost literally overnight, was not something that the infra team had planned on, which meant that every Friday at three o’clock, the site would go down.

Alfred Lin: There are just these natural times of the day where you’re ordering breakfast, natural times of the day where you’re ordering lunch and natural times of the day where you’re ordering dinner that becomes very, very busy. Do we have enough Dashers? Can we mobilize enough people?

Roelof Botha: In addition to meeting unprecedented demand from customers, DoorDash had to consider the other two sides of its marketplace: Would Dashers be willing to make deliveries? Would restaurants themselves even survive? How should DoorDash show up? It was the kind of crucible moment that not only determines your strategy, but clarifies your values and what role you want to play in the world.

Tony Xu: A lot of it has to do with what your beliefs and convictions are. I think this was true when we thought about how to differentiate a service in the earliest days to how we would show up during the pandemic.

So how do we secure and also distribute tens of millions of units of PPE to keep all Dashers safe? How do we ship no-contact delivery? How do we make sure that merchants can get liquidity immediately while keeping all of their staff safe? How do we make sure that consumers can get greater access?

How do we get free lunch to all the schools? How do we get free meals at all times to all of the doctors, the nurses, the staff at all of the largest hospitals? We partnered with all of the largest hospitals across the country to do that. It was a very just intense period of time for everyone, but it was also one that it was very easy to know what to do, right?

Roelof Botha: But there were also decisions that proved controversial.

Tony Xu: We cut our commissions by half. We were the only platform to do this, which at the time was controversial internally because we were not yet profitable, but this would have been a over $100 million expense. At the time, I think just about everyone on the management team was against that decision.

Keith Yandell: That was a hotly debated topic that maybe I was on the wrong side of history on. My take was, it’s going to cost us, I don’t know, $100 million. No one’s asking us to do it today. And if we’re trying to go public, that could be, at a 25x EBITDA multiple, you’re looking at a $2.5 billion in market cap we’re shaving off when no one’s asking us to do anything differently.

I was just saying, “Why don’t we wait and see?” Tony very thoughtfully listened to the debate, and at the end, there was absolutely no question in his mind. And he correctly said I was thinking a little short term, which I’m wont to do every now and then. And he said, “This is the right thing to do for our customers, and doing the right thing for your customers is never the wrong thing to do for the business.”

And I’ll never forget that. And I think it really not only helped to keep businesses going at a critical time but also helped people in the community view DoorDash a little differently.

Tony Xu: Advertising our competitors, I think, was a controversial decision internally. We spent millions of dollars buying a national TV campaign that was called “Open for Delivery,” where we highlighted us but all of our competitors as well, to tell consumers nationwide, “Just order—we don’t care who you order from.”

Alfred Lin: I think the question was, why collaborate across the industry? For every single one of these companies, it was hard enough as it is. We were competing with each other. I think all the food delivery companies were making very little margin on each delivery. And I think Tony just made this really compelling argument: “If we can’t collaborate during a crisis like this, when are we ever going to collaborate?”

And I think it was questioned for a hot second, and then you heard Tony’s compelling argument and his passion for helping the industry, and that’s the right thing to do. And I don’t think there was a question after that.

Tony Xu: I remember that when we advertised all of our peers, what ended up happening was on social media, you saw restaurants also advertising their peers and their competitors obviously. And I just thought, you know, that was not, you know, an outcome that we were forecasting and certainly not why we made the decision. But I think sometimes you kind of have to have the courage of your convictions just to make the decision without making any assumption that you’ll gain the benefit.

Alfred Lin: The pandemic became a crucible moment for DoorDash. This was a year where DoorDash showed its mettle and the ability to go even harder and stronger, and take a leadership position across the industry. We often use the race car analogy, where we talk about how you can’t overtake 18 cars on a sunny day because everybody is driving at peak performance, but you can on a rainy day. And during this crisis, this health crisis, DoorDash surpassed all its competition and became a market leader in the food delivery industry.

I would never say the pandemic cemented DoorDash’s market leadership. It helped propel it to market leadership, but there is nothing that is written in stone in business.

Expanding to Europe via Wolt Acquisition

Tony Xu: DoorDash has changed a lot over the last four years. You know, four years ago, in 2019, heading into 2020 and the pandemic, DoorDash was largely speaking a one-category—so restaurant delivery—business in one market, the United States.

Today, we have a portfolio of five businesses. So we certainly still have restaurant delivery in the U.S.; we also deliver in other categories in the United States, whether it’s grocery, convenience, alcohol or retail categories.

Roelof Botha: In June of 2022, the company began to consider another type of expansion.

Alfred Lin: Tony brought up the idea of expanding to Europe, planting a flag in a different region of the world. And the opportunity in food delivery in Europe was just as big as it is in the United States, and we just thought it was a good idea instead of going to Europe ourselves, to do that with a partner.

Keith Yandell: I was in Europe, meeting with various players in the space. We felt like we built a pretty good product and wanted to bring that to more geographies. And I hadn’t actually planned on talking to Wolt during that trip because they were pretty small compared to others.

Roelof Botha: Wolt is a Finnish delivery company founded in 2014 that operates across Europe and in parts of Asia.

Keith Yandell: I got a call from a mutual investor who said, “You’re making a huge mistake if you don’t stop and talk to these folks.” So I said, “Okay.” I got connected via email and went out and met Miki in Helsinki.

Miki Kuusi: Our goal was never to get acquired by anyone. Like our goal was just to build the strongest possible standalone company that we could, eventually go for an IPO and continue to build the company as a public company.

My name is Miki Kuusi. I’m the co-founder and CEO of Wolt.

In the fall of 2021, we were in the process of finishing a new round of financing, which was around $1.1 billion, which is when Keith Yandell, the Chief Business Officer of DoorDash, reached out.

Keith Yandell: Yeah, it took me about five minutes of talking to them to see cultural alignment. Just the way they talked about the business was so similar to how we talked about it. They came from a customer-first mindset. They were hyper-focused on retention. They had also been cash-constrained compared to their peers, which led to them having the best retention we had seen by a pretty wide margin.

At the time, for us, the most scarce resource had moved from cash to executive bandwidth, and so, we were really looking for a team that we thought could help us from a team perspective as much as anything else.

And meeting Miki, I knew immediately that they could up-level our execution outside of the U.S.

Miki Kuusi: I remember telling my COO after the meeting with Keith like, “Man, I’d like to hire that guy,” which is a good signal about culture fit.

We were never really serious about proceeding with DoorDash. We kind of saw it as a learning opportunity. But ultimately, through that process of getting to know Tony and the DoorDash team better, and talking about the industry and what kind of company we wanted to build and so forth, we kind of realized that with Wolt, we could build a leading company in our industry globally. But with DoorDash, we kind of saw the opportunity that we could build the leading company in our industry globally.

Roelof Botha: DoorDash’s acquisition of Wolt closed in June 2022.

Keith Yandell: So, we had acquired some companies in the past. We acquired Caviar in 2019. That was a much smaller business. We were co-located, both in San Francisco. There was no time zone differences. There were cultural differences, but not cross-border cultural differences. And Wolt brought all of that complexity of operating in near 30 incremental countries across a nine- ten-hour time difference, into focus for us—and it was a whole different kind of challenge.

Tony Xu: I was concerned about whether or not we can make the Wolt partnership successful. I mean, on the one hand, it was very large in size and I think secondly, these types of businesses, they’re very local in nature. They’re very highly operationally complicated, and that’s really hard to do—country to country to country to country to country. And so, there were a lot of risks that presented themselves, when it came to partnering with Wolt.

It was a very big partnership, especially for a company like DoorDash that doesn’t tend to do much in the world of M&A. But it was one where you’re bringing together two very like-minded teams that coincidentally had gone through very similar challenges I think in how they were forged through the fire of being under-resourced relative to their peers and in getting to category leadership.

And then, I think, you know, it was just two groups of people that had the same vision for what the end state is in terms of what we want to build together, but also the same, you know, beliefs on how we should build the company to get there. I think it’s really hard to find those types of, you know, partnership opportunities.

And so we’ve been thrilled with the partnership thus far. It certainly was a big move, but it was one that has really paid off.

Lessons From the Journey

Alfred Lin: There are many lessons from DoorDash’s story. One, for me, is to dream with the entrepreneur. I think it was easy for me and my partners to dismiss DoorDash as just a food delivery company, but they were already at the seed talking about being the FedEx of local delivery—all the way back then. Instead of trying to think small, we should just think big, and to turn down a company like DoorDash at the seed or the Series A purely because you don’t believe… Sometimes, you just dream with the entrepreneur and just believe. Be a believer.

Tony Xu: Our Demo Day pitch of Summer 2013—it is the same pitch we have for the company today, which is we believe ultimately DoorDash is going to be the infrastructure for how all things get moved around inside of a city, where we will connect every local consumer to every local business.

And I think in life, the only real way to grow is to do the thing and take all of that comes from it—you know, all of the challenges, all of the mistakes that might be made, and, you know, also all of the successes you may have from doing those things. I’m not sure there’s any other way. So, you know, first and foremost, when I think about all of the tough times, or especially the tough times that Doordash has had, I’m quite grateful for them. There’s no way that DoorDash would be where it is today without those challenges—really no way.

And it’s very possible, and I could see in an alternative world, where had we not had those challenges, perhaps we wouldn’t be in the position that we are in today. You know, I really believe that these championship habits start early, and they tend to get built when you have a team around you that really believes in the same things about what excellence looks like, as well as the broad strokes of how to get there.

I think the team camaraderie, as well as just, you know, the lessons that we’ve learned in terms of how do you evaluate some of these very consequential decisions that almost always come with conflict and pain in the short run—that is very quantifiable—with an unknown gain on the other side that’s quite uncertain.

And I think, you know, especially as an entrepreneur, a lot of times we are a basket where we only have one thing we’re wholly committed to. And so, you just have to make it great.

Roelof Botha: This has been Crucible Moments, a podcast from Sequoia Capital.

**

Crucible Moments is produced by the Epic Stories and Vox Creative Podcast Teams, along with Sequoia Capital. Special thanks to Tony Xu, Alfred Lin, Keith Yandell and Miki Kuusi for sharing their stories.