A Startup Founder To Scaleup CEO’s Journey from $0 to $25billion (Halliganism’s)

In my work as an investor with Sequoia and Propeller, many CEOs pick my brain about the journey from startup founder to scaleup CEO. It was indeed a long strange trip, but one on which I learned a lot. Here’s a list of Halliganism’s I picked up along the way that I hope will help some of you on that same journey.

Leading

Perspiration vs Inspiration: In startup mode, the CEO role is 90% perspiration and 10% inspiration. In scaleup mode, the CEO role is 10% perspiration and 90% inspiration. What worked in startup mode won’t necessarily work in scaleup mode—you’ll need to evolve.

1 back, 2 forward, 1 back, 2 forward: From the outside, HubSpot might seem like a smooth up-and-to-the-right story. It belies what actually goes on inside. The best way I’d describe HubSpot is two steps forward followed by one step back followed by two steps forward followed by one step back over and over. We never found that “silver bullet.” There was never one hire, one customer, one partner or one investor that moved us forward more than two steps. It’s a grind.

A perpetual state of constructive dissatisfaction: This is how one of my board members, Lorrie Norrington, described me once. I kind of liked it.

Manage your trust battery carefully: As a CEO, you generally start out with a fully charged trust battery. Over time you make calls—you get some right and get some wrong. If you get too many wrong in a row, you lose a lot of the charge in the trust battery with the organization and along with it some of your moral authority. My rule of thumb is that you get a few “CEO cards” to play that may be very bold bets or ones that your team disagrees with. You don’t have 52.

Keep your head in the sky and your feet on the ground: You need to paint a compelling vision of a terrific future for your company while at the very same time dealing head on with the very real problems you have today. Toggling between those two is a delicate dance that takes some feel to get it right. …Btw, if you give your investor the line that you “focused on the terrific future and not to worry too much about this quarter’s numbers,” prepare for them to vomit on your sneakers. [h/t Teddy Roosevelt]

I was a wartime CEO: There were times in HubSpot that were relatively peaceful and times that were more like war. I felt much more comfortable during wartime. During peacetime, decisions bubbled up from the bottom and were made more deliberately. During wartime, decisions came from the top down and were made more quickly. Knowing whether you are in wartime or peacetime is useful. Knowing which mode you thrive in is also useful …Imho, the h/t goes here to Ben Horowitz who coined this term, but I think Paul Graham kind of picked up the thread with “founder mode.”

Culture

EV>TV>MeV: It is critical that everyone in the organization solve for the “Enterprise Value” over their “Team’s Value” and over “Their Own Value (MeV)” when they are making decisions. I found that when I wasn’t watching closely, leaders would solve for their “team’s value” over the “enterprise’s value” and often when they solved for their team’s value, that sub-optimized another leader’s team’s value. Like many other things, this is a tax that creeps into the organization as it grows (#ScalesTax) and needs to be fought.

Your culture is your second product: At HubSpot, we have two products: one we sell to our customers (HubSpot’s CRM), and one we sell to our employees (HubSpot’s culture). Like your product, you need your culture to be unique relative to the competition (for talent) and you want your culture to be very valuable (for talent). Like your product, when your culture is unique and valuable, your company turns into a magnet that attracts and retains terrific talent. And also like your product, it’s never done—it needs continuous iteration.

Customer OR Employee OR Investor: I think every company is either customer centric (Amazon), employee centric (Nvidia), or investor centric (Berkshire Hathaway). This usually comes from the CEO. If you want to change it, you need to work hard to do that. In HubSpot’s case, our first 8 years we “talked the talk” about being customer centric, but if you looked at what we spent our time on, we were actually “employee centric.” This had its benefits, btw, and isn’t a bad way to go ( see Nvidia), but we felt we needed to walk the walk and be customer centric. Around year 8-ish we made a conscious choice to make that shift and it worked pretty well. We largely did this through more carefully managing the agenda in our management meetings, changing the incentives for our bonus (i.e. added NPS), moving money around the P&L from S&M to R&D, etc.

Keep an eye on the mercenary to missionary ratio: When you are in the early stages of your startup, almost everyone you hire is a missionary. As you scale, more and more of your employees will be mercenaries, but not all, of course. I think you can do things to delay the shift, but it is pretty inevitable and you should live it with. There are plenty of companies that scaled just fine before yours with a mix of missionaries and mercenaries. #ScalesTax

Your org will naturally become more risk averse as you scale: When you are in the early stages of your startup, almost by definition, everyone you hire is very risk seeking and is willing to be very bold to create a lot of upside. After all, there’s very little downside to protect! As you scale and have something to lose, the organization will protect that. This is a natural thing that happens to existing employees whose net worth is improving – I don’t blame them. This is a natural thing that happens to new hires when they look at your brand on their LinkedIn profile as part of the decision to join you – again, I don’t blame them. In our case, my cofounder is preternaturally risk seeking and was always a very good counterbalance to that trend toward risk aversion.

Cultures typically “break” around 150 employees (Dunbar’s number): Our culture broke around this size and almost every other CEO’s company I talk to did too. I think it is a combination of the missionary ratio, some risk aversion, the fact the founder didn’t interview everyone, and that there is a new layer of management. Getting through that in one piece is kind of where you move from a startup to a scaleup, imho.

I tried to kill titles and org charts: At one point, I drew on a whiteboard near my desk at HubSpot what I thought was the “influence chart” as a counter to the “organization chart.” It looked much different and actually showed a guy named Brad Coffey as the most influential person inside HubSpot, not me. Around the same time I tried to eliminate titles. There was a huge amount of pushback and I decided these weren’t the hills I wanted to die on. I suspect you’ve thought of the same thing. If so, may the force be with you.

Team

Times change, teams change: Our original management team at HubSpot was brilliant and I just assumed it would be the same crew we’d be in the trenches with for the whole run. That turned out not to be true. If you step back, you’d see that we are probably on our third or fourth management team – all were good in their respective stage. It turns out that people kind of self-select for stage. Those early leaders we had were super risk seeking and really well suited to that phase and have all gone on to do awesome stuff in that early stage. I’m super proud of them.…My advice is not to sweat it too much if you need to replace leaders on your team as you grow. The company and the leader are likely both better off.

Recruit from companies just a few years ahead of you: I’ve found this applies to board members and executives. When we hire folks from companies that are several orders of magnitude larger than HubSpot (i.e. Microsoft, Google), there is an impedance mismatch. They are dealing with different issues at a different scale. We’ve had good luck with hiring folks who are at companies we admire that are just a few steps ahead of us.

A truly independent board member is worth her weight in gold: We have had several along the way from companies that were ahead of us in size, but still growing fast. Along the way, they helped us avoid untold landmines as they had “already seen the movie.” The other benefit of a truly independent board member is she is typically a good counterbalance with your venture capitalists. I found it helpful to have sourced the independent board member myself as opposed to having it come from the VC’s tight circle.

Home grown talent is underrated: I’ve noticed that the vc playbook when a new round is done is to recommend “upleveling” some of the home grown talent. In some cases this might be right, but I think folks over index on it. If you look at the executive teams of some of the best companies (i.e. Apple, Nvidia, Amazon, etc) they are full of people who have been there a long time. HubSpot’s current management team has a lot of “home grown” talent.

Build your team like the 2004 Red Sox: The Red Sox went 86 years without winning the World Series. In 2004, they finally won it with a ton of home grown talent and few seasoned veterans that put them over the top, like Pedro Martinez, Curt Schilling and David Ortiz. HubSpot often had a lot of home grown talent on its senior team and usually had a couple of well placed veterans that put them over the top.

You can’t teach someone how to be smart: Tommy Heinsohn was a former Boston Celtic great who was an announcer for the team. I remember him talking once about a backup center for the team who was 7 feet tall and had some girth. Tommy said, “you can’t teach 7 feet.” He had a good point. That player wasn’t highly skilled, but he was huge and that was in and of itself quite valuable. I feel the same way about brain power. I used to look around the table at management team meetings and think about whether each person was empirically smarter than I was. I always wanted to be the dumbest guy in the room and largely succeeded at it.

Avoid compliments. Find complements: If I put 100 calories into getting better at something I was already kinda good at and enjoyed, I would get 1000 out. If I put 100 calories into getting better at something I was kinda bad at and didn’t enjoy, I would get 101 out. I stopped obsessing about fixing my weaknesses and started hiring folks that could plug them. Don’t hire in your own image! Hire folks who are complementary.

It was mostly product and sales: In scaleup mode, I spent most of my time on product and sales and didn’t give much attention to things like legal and finance. This was “unpopular” with folks in legal and finance and probably led to some unfortunate turnover of some good people.

Five compliments for every criticism is bull-shiitake: Management gurus will tell you that you need to give five pieces of positive feedback from every correction. If this is true, I had it all wrong and so did everyone I ever worked for.…Related to this, the feedback sandwich, the one where you surround your negative feedback with positive feedback before and after it is also bull-shiitake. Everyone knows this game—it doesn’t work anymore.…I’ll be pilloried for this, but this was my lived experience.

Jensen Huang is mostly right about management, imho: In the early days of HubSpot, I liked big, relatively infrequent meetings (monthly, not weekly) where everyone could hear what was on my mind, avoided the weekly 1:1, and I would criticize and compliment in public. As time went on, I started doing closed weekly meetings, having 1:1s, and I stopped criticizing in public. Listening to how Jensen runs Nvidia leads me to believe I wasn’t completely crazy to run it the way I did back then.

Analytical skills are overrated. Taste is underrated. Almost everyone these days has pretty good analytical skills. Vanishingly few people have taste. Figure out who has it and give them power.

Exec Hiring Success Rates Are Lower Than You Think: If I look at all of our executive hires over time, I’d guess that 18 months after that senior hire happens, around 60% of them have “stuck” and we end up churning about 40%. This is similar across most of the CEOs of companies I coach. Senior level hire candidates are very good at interviewing. Interviewers of senior level hires, including myself, overestimate their skill in interviewing. My advice would be to reduce your interview panel and hire the folks who have great strengths (4/4s) and maybe some weaknesses (2/4s) while avoiding the candidates who are all “good” (3/4s). In other words, hire for strengths, rather than for a lack of weakness. …If you whiff on one or two big hires, don’t sweat it too much.

You need glue people to scale: This is a term used in sports to describe players on team sports who aren’t the stars, but are the glue that makes the teams really get over the top and win. I think it applies even better to scaleups. As we grew, the leverage really shifted from star players to glue players who really knew how the machine worked and were “ops” wizards. For example, in startup mode, the leverage is with your top sales reps and leaders, but the lever shifts to that quiet ops person who can turn the right knobs and dials and not break the machine. [h/t Ravi Gupta from Sequoia]

Strategy

Watch the competition, but never follow it: I got this line from Arnoldo Hax, my strategy professor at Sloan, and repeated it so many times that it is ingrained in HubSpot’s DNA. It is relatively obvious at this point that HubSpot competes with Salesforce.com (a formidable competitor). We very carefully watched them, but tried not to “follow” them—see next lesson.

When everyone is zigging, you should zag: Regardless of what you think of Peter Thiel’s politics, he wrote a really good book on startups called Zero To One. In it, he talks about how you need to be right about something that everyone thinks you are wrong about for a long time. This type of “zagging” worked for HubSpot three times. First, we decided to focus on SMB (more M than S, btw) and stuck with it when everyone and their brother thought we should move to the enterprise. Second, we decided we would move from a marketing application company to a CRM platform company, competing with Salesforce, when everyone and their sister told us we were crazy to try because they were too hard to compete with. Third, we decided we would “build” (craft!) our CRM in-house as opposed to acquiring our way there when everyone and their cousin told us that we needed to follow ye olde CRM M&A franken-playbook.

Don’t trash talk: I recently watched the U.S. Open tennis finals. In the remarks after the matches, I always appreciate how respectful the players are toward their opponents and how they express it. I feel the same way about Salesforce; they are a very good company that is hard to compete with, and no good comes in “poking the bear.” [h/t to my co-founder Dharmesh for coming up with the “poke the bear” analogy and many other brilliant things]

Creating a category is harder than it looks: HubSpot created the “inbound marketing” category. Pulling that off involved writing about zillion blog articles, giving a jillion speeches, writing a book, running a conference, etc. We invested way more energy in creating the inbound marketing category in the early years than we did in marketing the HubSpot product. …So, when we wanted to go into the sales category, we thought we could just re-run the same playbook for “inbound sales.” Failed. When we went into CRM, we thought we’d create a new category called CMR, “customer managed relationship” software. Failed. When we released our CMS, we thought we’d create a new category called COS, “content optimization system.” Failed. In retrospect, we caught lightning in a bottle with “inbound marketing.”

Either you are eaten by a platform or become a platform: In the early days of HubSpot, we used to pitch the company as “Salesforce.com is to sales as HubSpot is to marketing.” Under our breath, we’d always say “until Salesforce.com wants to become the Salesforce.com of marketing.” Well, one day they did. They picked up Exact Target, Pardot, Radian6 and Buddy Media all within a few months and built themselves a very large Marketing Cloud business. We decided at that point that we ought to pivot from being a marketing app to a CRM platform ourselves, lest we be eaten. This turned out to be a very good call in hindsight. [h/t Steve Fradette, co-founder of Toast]

Decision Making

Compromise is the enemy of greatness: As a CEO, you are often in the middle of roiling debates about any number of things where there are really good arguments on both sides. The temptation as a first-time CEO surrounded by senior and smart folks is to make people happy on both sides of those good arguments and craft an “uninspired compromise.” This is the kiss of death. You want to actually break the tie. You want the argument at hand to have “winners and losers.” [h/t Brad Coffey]

Wearing NO shirt!: As a new CEO with lots of money in the company’s bank account, I wanted to do all the things. I found myself saying “yes” a lot. This caused a lack of focus which led to shoddy execution and budget problems. I got some pointed feedback about this and wanted to change, so I made a literal “No” shirt and wore it to management meetings. People got the point that I wasn’t just going to rubber stamp every good idea.

If you want to kill a plant, have two people water it: If you ask two people to look after your plant while you were away for a month, it would likely struggle due to over or under watering. If you ask one person to look after your plant while you were away for a month, it would likely flourish. Whenever we assigned multiple people to own a project, it almost always went sideways. The DRI concept certainly wasn’t novel to us, but when we ignored it, we suffered.

Sometimes doing nothing is the right thing to do: I think a lot of CEOs have a “bias to action.” I think this is mostly good, but when you are short on staff and have a ton going on, it is often best to sit on your hands and let folks keep grinding on their projects and not jerk the steering wheel. I jerked the steering wheel too much.

Avoid the “Tyranny of Or”: We used to do an annual field trip with the management team to the west coast and meet with execs we respected to just learn. One year we visited George Hu. He was the former COO at Salesforce and was then at Twilio (I think). He encouraged us to challenge our teams to avoid the “Tyranny of Or,” like you can have it fast or you can have it good or you can have it cheap. I started pushing back on the “or” framing in meetings and was kind of surprised that it actually worked sometimes. Thanks George.

Nap on it: If too much food comes into my mouth, my stomach gets full. If too much information comes into my head, my brain gets full. I’m definitely someone who gets major duomo decision fatigue! To combat that, during a day where there was a lot of information flying around, I’d sneak out to our nap room (yup) and get a quick 20 minutes in. When I’d lie down, I’d be thinking about the decision at hand and when I’d wake up, often I’d have some clarity on it. I think of a nap as a time when my brain cleans up—sweeps the debris, organizes the files, etc. When things are cleaned up, I’m better able to make a call.

“Get to the coal face”: This was an expression one of my VCs, David Skok, used one day that I pretended to understand, but didn’t. I googled it later on: “The place where the actual work of an activity is done. For example, ‘Those at the coal face of the business may lose patience with theories and abstractions.’” It turns out that the bigger the organization gets, the further the CEO gets from the front line employee and the customer. It used to drive my managers crazy, but I’d often jump several levels down in the organization and try to get the coal face truth from the sales reps or support reps who were talking to customers every day. I also used to have customer panels at all of our management meetings and some of our board meetings to keep everyone grounded in what the customers were actually saying. I did a lot of stupid things at HubSpot; this was smart.

Crisis management

Never waste a good crisis: There were tons of problems and crises along the way. One of the things that served HubSpot particularly well is that we recognized the crises when they were happening and were explicit about trying to take advantage of them to learn and get better. During a crisis, we’d literally say outloud over and over, “let’s not waste this crisis.” Ironically, one of the best “crises” that happened to us was a long outage on the last day of the first quarter in 2019. It led us to make comprehensive changes to the way we built and delivered products, and helped enable us to move the culture to becoming even more customer centric. As awful as Covid was for humanity, it was that crisis that gave us cover to make some wholesale, healthy changes to our business model. Crisis = Opportunity.

When you have to eat a shit sandwich, don’t nibble: This is an idea I heard from Ruth Porat, the CFO at Google, that rang true to me. Where I got in trouble was when I spun things to employees, customers, partners, etc. People are smart and they are paying very close attention to what the CEO says. If you spin them, you’ll regret it. It’s better to take a giant bite out of that shit sandwich now than have the whole thing shoved down your throat later.

Listen to Coach K: The winningest coach in men’s basketball was Duke’s Mike Krzyzewski. The thing that drove him crazy was when someone would miss a shot on offense and then compound it by making a dumb play right after on defense by taking a stupid risk to make up for the missed shot. You could hear him on the sideline yelling (imploring) after every missed shot “Next play… Next play.” I used this method several times following unforced errors, including my own, to try to get the company to put the past in the past. I think it mostly worked. Thanks, Coach K.

Improving Your CEO Craft

Feedback is the breakfast of champions: Once a year we had my co-founder, Dharmesh, do a 360 review for me that was like pure gold. His method is highly replicable. He gave an NPS survey to about 25 folks up and down the org asking two questions: (a) “Your likelihood to recommend Brian as the CEO of HubSpot” and (b) “Why?” He took the answers to those questions and put together a 20 page document for me. He found the themes in the feedback (people wrote novels!) and grouped them together with example quotes to back up the theme. For example, “Brian is good at setting and selling the vision for HubSpot” would be the theme and then he’d pick out 6 or 7 direct quotes that backed this up. …Now, not all the themes were positive like that one. The first 10 pages were my “feature” themes and the back 10 pages were my “bug” themes. I was convinced I was the world’s best CEO after page 10 and the world’s worst CEO after page 20! I shared the document with the company and board along with my own “performance plan.” I’m not sure, but I “think” it might have inspired HubSpotters to take their own improvement more seriously.

Your greatest strength turns into your greatest weakness: Starting up is doing as many jobs as possible so your company can survive. Scaling is shedding as many jobs as possible so your company can survive. [h/t Aaron Levy] Even founder mode types need to delegate, particularly on things that aren’t super core.

I benefited from CEO groups: When we were an early stage startup, I was in a CEO group. One of the CEO’s was Colin Angle from iRobot – he had a whopper influence on a very young and raw version of myself. After we scaled, I joined a CEO group with a bunch of terrific public company CEO’s from companies like Slack, Atlassian, Shopify, etc. Half of the value of these CEO groups was a collective “misery loving company dynamic” where we all shared our problems and all our problems rhymed. The other half of the value was getting best practices on how to solve those problems.

I benefited from a CEO coach: At one point my board suggested I hire a coach. Ahem. Strongly suggested I hire a CEO coach. This turned out to be a good idea. He was half coach and half psychologist. I need both!

Communicating

Get the truth telling vs cheerleading thing right-ish: I worked with folks who were always cheerleading and didn’t spend enough time grinding on the details. It drove me crazy. I tended to over-index the other way. It drove many of my people crazy. My advice is to check yourself on this from time to time and not over index one way or the other.

Transparency builds trust: We were always very transparent with employees, customers, partners and investors. When new execs would come in they would always be surprised at our level of transparency and a little uncomfortable at first.…I think that transparency built trust with all our constituencies. Filling that trust battery helped in innumerable ways..

It’s not 10,000 hours, it’s 10,000 times: In the early days of HubSpot, I remember sitting in the audience at Dreamforce listening to Marc Benioff tell the “cloud story.” I remember wondering to myself how many times Marc had told that story. It must have been at least 10,000 times. Whenever I was getting bored telling the “inbound marketing” story, I’d take comfort in the fact that it took 10,000 times to sink in. This was also true for the story of HubSpot moving from a marketing app to a CRM platform—at least 10,000 and still counting!

I lived presentation to presentation: In the early days as CEO of HubSpot, I felt like I lived from one presentation to the next. I was always working on my next presentation—an updated customer pitch, a company meeting presentation, a board meeting presentation, an Inbound conference talk, etc. I was always, always, always working on a deck.

You’re being watched 10x more closely than you think: I often hear from HubSpotters about something I said 10 years ago in a hallway conversation that I had long forgotten. It may not seem like your team pays any attention to you (it seemed that way to me), but they are very closely observing what you say and your body language. This can be a superpower or kryptonite for you.

You need to absorb complexity and pass down clarity: Inside the walls of HubSpot at any given time, there was anywhere from a few light wisps of fog to a full on San Francisco style fog bank socking us in. The job of the CEO is to do a good job of “clearing that fog” and I found myself frequently in meetings where the topic was “clearing the fog on ____.” My colleague JD Sherman used to walk into those meetings and say “the job of a leader is to absorb complexity and pass down clarity” and I think he was right about that.

Managing Yourself

Work and life never balanced for me. I’ll probably be pilloried for this, but I never had work-life balance and never really had a “real” vacation. Being a CEO was a full contact sport and I chose it over balance more often than not. The truth is, I don’t regret it. I have come up short on some of my personal objectives, but have far, far exceeded my professional objectives. My life’s been really good so far.

Work can be a lot of fun: I see a lot of CEOs these days with their teams and sit in a lot of board meetings. Honestly, there aren’t a lot of laughs! This is interesting to me because HubSpot’s management meetings and board meetings were always pretty serious, but there was also almost always a ton of levity, even and especially when things were going sideways. Some of the funniest moments of my life were work-related. My former HubSpot colleague, JD Sherman, might be the funniest person I know and my cofounder isn’t far behind him.

Be yourself; everyone else is taken: I worked for three different CEOs prior to doing it myself. They couldn’t have been more different. I joined a CEO group with 8 other CEOs. They were all pretty different. I tried to be like other CEOs for many years. Over time as I got a bit more confident, I just tried to be myself, quirks and all. Folks didn’t seem to mind me much most of the time. [h/t Oscar Wilde]

Imposter syndrome didn’t go away: Even today as I’m typing this article, I feel major imposter syndrome. If you’ve got it, you’re not alone. If you don’t, I’m jealous.

Make a large pizza and take a slice out along the way: One thing Sequoia did in our Series D round was allow us to sell some of our common shares to them as part of the round. This turned out to be a great idea for me (and even better for Sequoia!). It “stiffened” my backbone when it came to acquisition interest and kept us focused on building a company our grandkids would be proud of. This had the added benefit of aligning our interests very well with our investors.…In retrospect, it was likely one of the worst financial decisions I’ve ever made, but I don’t regret it. The liquidity then was great (I’m typing this from the home on Cape Cod it bought me back then) and the pie was plenty big.

Exits

We didn’t get any acquisition offers: I always thought that every scaleup had multiple offers multiple times for acquisition. Maybe they do. We didn’t! …The likelihood you are going to get acquired for a good price by your dream acquirer is really low and is even lower these days with the regulatory environment. Build something that you think your grandkids will be proud of decades from now.

The IPO is the starting line: The day of the IPO was one of the best days in HubSpot’s history—lots of laughter and a lot of tears as well. In the years leading up to the IPO, I repeated the line “the IPO is the starting line” hundreds of times and I can’t say for sure, but I think it kinda worked. I wanted folks focused on building something special that ultimately our grandkids would be proud of.…The other thing I did is I never talked about the stock price and would ask folks around me to stop talking about it whenever I heard those conversations. Focusing on the price will drive one bonkers—it has a lot to do with our performance, but it also has a lot to do with many things out of our control.

Going public is underrated: Now that founders are able to get liquidity prior to going public, there is less allure in the IPO. I get it. What I think people underestimate is the pure joy the actual IPO gives you and your team. The day of the IPO and the party we had the day after were among the happiest and most gratifying moments of my life.

Planning

Aligning vectors is actually magical: This is something I “borrowed” from an Elon Musk talk at a Sequoia event a few years back. He describes each employee as a vector with a strength and a direction. In most companies, these vectors are pointing all over the place. One the top of the list of jobs of the CEO of a scaleup is to hire folks with strong vectors and point them all in the same direction. Here’s how I think about it:

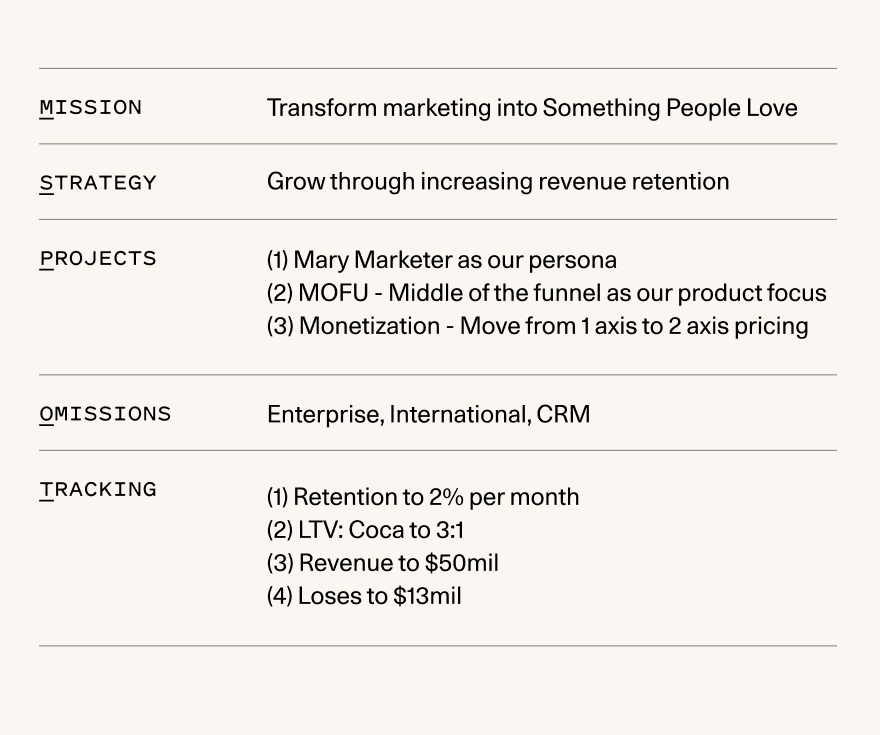

MSPOT–the planning doc to rule them all: We visited lots of companies to ask about planning and looked at all kinds of methodologies. We came up with our own, we called MSPOT that enabled us to get our vectors aligned. Mission, Strategy, Projects, Omissions and Tracking. The thing I liked about it was it got everyone to argue about and agree on a few key priorities and how to measure them, and it put everyone’s pet rocks on the shelf until the next planning period. HubSpot’s first MSPOT from 2012 was something like this:

Use 6 Month Planning Seasons: When we were in peacetime, we benefited greatly from planning “seasons.”

- April to June: Long range strategy planning and navel gazing

- July to Sept: Turn long range plan into next year’s plan

- Oct to Dec: Budgets

- Jan to Mar: Heads down on Q1 plan

These seasons avoided constant churning around different strategic directions and allowed a place for everyone to bring up their pet rocks and where to put those pet rocks to bed. In retrospect, I think I would have done these biannually because we’d often edit the plan halfway through the year. It turns out that the 365 day earth-sun cycle doesn’t match the earth-technology cycle.

Complexity kills: Complexity creeps into the organization as it scales. It’s like gravity. My advice would be fight it tooth and nail in HR policy, compensation plans, pricing policies, etc. #ScalesTax

The more people you have, the less you get done: This is another one of those gravity things. I used to look at our priority list every year and it got shorter as we got bigger. I learned to be okay with it—we got most of the big things right most of the time.

Stepping Away

Know when to hand over the keys: One day in 2021 I had a very bad snowmobile accident that nearly took my life. Lying in the snow badly injured, I had some time for introspection while waiting a long time for 911 to arrive. I basically decided while lying there that I didn’t want to be CEO of HubSpot anymore. I wasn’t getting the joy out of it I once did and I didn’t think the next phase of bringing HubSpot from $2 billion in revenue to $10 billion in revenue suited my skills very well. I stewed on that for a while and then when I recovered about 6 months later, I handed over the keys and became chairperson of HubSpot.

Pick your successor carefully: I ended up handing those keys to Yamini Rangan who has done a terrific job. There are a few reasons she was a good fit. First, we worked together for a while and I got to know her—we promoted her from within. Second, prior to HubSpot, she worked at Dropbox and Workday, two companies that, at the time, were “a few steps ahead of us.” Third, while I was out on medical leave, she did a great job of running the company on my behalf….I hope none of you CEOs have to go through a near death experience to decide to step down, but I might encourage some introspection on when that right time might be for you. Most wait too long, imho.

Chairpeople Don’t Drive: Once I took on the chairperson role, I talked to several other founders who have gone through similar CEO transitions and taken on chairperson roles. The one thing I heard from everyone was to “let go of the steering wheel.” Chairpersons and board members are the grandparents and the CEO is the parent. The failure case is that the chairperson has to go back in and be CEO again à la Howard Shultz at Starbucks.

Being CEO is overrated: A lot of people want to become a CEO, including me 18 years ago. I’d just tell you that it is an overrated job. You work for everyone: your customers, partners, employees and investors. It’s not the other way around. You are on call to them at all times. Be careful what you wish for!

Hope these help you on your journey.