The Game Theory of AI CapEx

“Will AI change the world” and “Are CapEx levels too high” are different questions.

Imagine you knew for certain that AI was going to be as transformational as the internet, and that you control the only AI company in the world. How fast would you build CapEx?

I believe the answer is: You would take your time. “AI CapEx” is a euphemism for building physical data centers with land, power, steel and industrial capacity. If you were the only company in AI, you’d wait to digest some AI revenues. You’d see how liquid cooling systems perform, and alter your data center designs as needed. You’d build new power generation assets in the right locations, and then build your data centers in proximity to fiber optic cables. What you would not do is immediately lock in multiple years worth of CapEx, because you’d know that as models and architectures shift, so too will your data centers need to evolve.

Many market participants today would have you believe that there is a choice between being an “AI bull,” who believes that infrastructure building is justified by AI’s enormous potential or an “AI bear,” who believes that overbuilding sets future expectations too high. The thought experiment above illustrates that this is a false dichotomy. The CapEx debate is a debate about speed, not about magnitude.

In fact, the more you believe in AI, the more you might be concerned that AI model progress will outpace physical infrastructure, leaving the latter outdated. For example, once everyone has 100k clusters, big tech companies will need to figure out what to do with their 50k and 25k clusters. We’ve heard a few industry experts make comments along the lines of: No one will ever train a frontier model on the same data center twice—by the time the model has been trained, the GPUs will have become outdated, and frontier cluster sizes will have grown. There is also the issue of how much power you need for a given real estate footprint and how dense to pack your GPU racks, decisions that are dependent on GPU power efficiency—a moving target.

The key to understanding the pace of today’s infrastructure buildout is to recognize that while AI optimism is certainly a driver of AI CapEx, it is not the only one. The cloud players exist in a ruthless oligopoly with intense competition. This is no small prize to defend—the cloud business today is a $250B market, roughly the same size as the entire SaaS sector, combined. The cloud giants see AI as both a threat and an opportunity and do not have the luxury to wait and see how the technology evolves. They must act now.

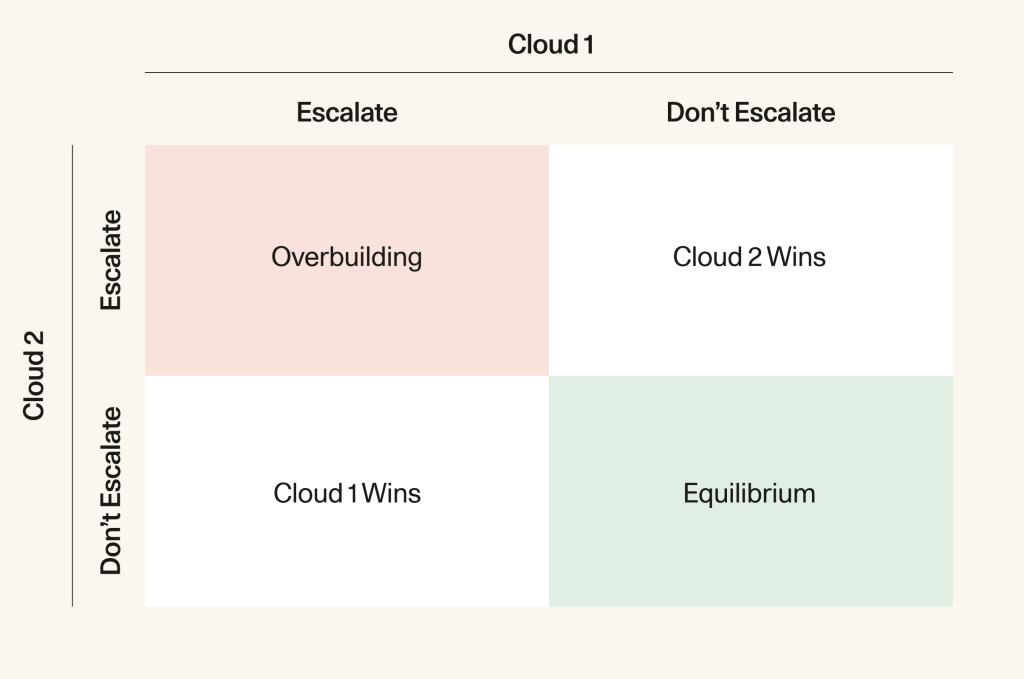

The arms race between Microsoft, Amazon and Google is thus game theoretic. Every time Microsoft escalates, Amazon is motivated to escalate to keep up. And vice versa. We are now in a cycle of competitive escalation between three of the biggest companies in the history of the world, collectively worth more than $7T. At each cycle of the escalation, there is an easy justification—we have plenty of money to afford this. With more commitment comes more confidence, and this loop becomes self-reinforcing. Supply constraints turbocharge this dynamic: If you don’t acquire land, power and labor now, someone else will.

For smaller players, the urgency is even higher. If Microsoft and Amazon buy up all the land and power, buy up all the diesel generators and buy up all the liquid cooling systems, then how will you compete? When you look one notch below the scale of Amazon, Google and Microsoft, there is a sense of desperation. If you do not move now, you will never get another chance.

This helps explain another potential motive for the aggressive behavior we’re seeing from the cloud providers: Defense. There is a real-sense in which only companies that have the balance sheets to withstand big write-offs can now afford to play in the AI infrastructure race. From this perspective, overbuilding may be perfectly rational.

Whether for reasons of optimism or reasons of competition, today’s rapid construction of new AI data centers should have a big positive effect on startups going forward. Much of the risk in AI today is being borne by infrastructure providers. This is effectively a subsidy for the startups who are building on top of them. Competition between Microsoft, Amazon and Google should assure lower API pricing in the future. It’s also good for the AI ecosystem—these CapEx investments will enable us to test scaling laws and learn more about AI’s future potential.

Like governments did in the past, big tech companies are making high upfront infrastructure investments that will spur innovation. Whether or not these investments end up being profitable before they depreciate, they are on the critical path to AI’s long-term impact.