Nvidia: An Overnight Success Story 30 Years in the Making

The AI revolution has been the biggest story in technology over the last year, as the stuff of science fiction turned into reality seemingly overnight. At the center of it all is Nvidia, a company that until a few years ago was known mostly for video game graphics. A full decade before ChatGPT launched, Nvidia began mobilizing to power the computing potential of AI. Nvidia’s pivot toward AI computing is one of the most remarkable business pivots in history. Hear the whole story directly from founder and CEO Jensen Huang, along with longtime board member Mark Stevens and AI luminary Andrew Ng.

Listen Now

Key Lessons

Nvidia founder and CEO Jensen Huang transformed a niche player in the nascent gaming industry in 1993 to the powerhouse of the AI revolution as the third most valuable company in the world. From near-bankruptcies to pivotal technological breakthroughs, Nvidia’s story is a textbook of unexpected lessons for founders.

- Decide on your first principles, and then just start. If first principles say you’re right about a non-consensus view of how the future will work, bet on it. Jensen Huang and his co-founders reasoned that the pace of computing would outstrip CPU capacity and make their GPUs inevitable. Huang advises, “If you believe this is going to change the computing industry altogether, for what reason don’t you take this first move? Just start.”

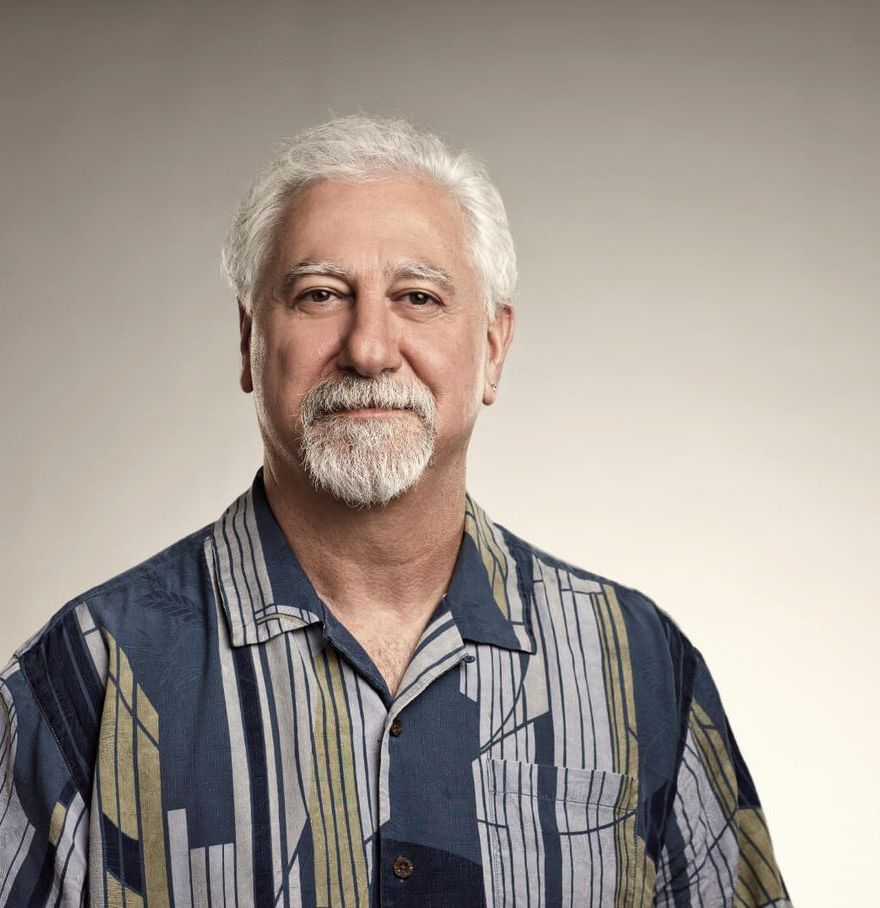

- Take the (very) long view. It took six years and three product lines for Nvidia to find product-market fit. It took 3 decades for their vision of transforming computing with a new paradigm of accelerated computing to come to fruition. Building a company like Nvidia takes endurance, and resilience along the way. As co-founder Chris Malachowsky reflects, “It feels like this overnight success was 30 years in the making.”

- Pay attention to unexpected ways people use your product. When Jensen and his team began hearing murmurs that researchers were adapting their video game GPUs for other kinds of computation, they embraced it, and pivoted the whole company toward powering AI. Huang recalls, “researchers realized that by buying this gaming card called GeForce, you add it to your computer, you essentially have a personal supercomputer.”

- Network effects even benefit hardware. Before the pivot to AI, Nvidia introduced CUDA, a software platform that lets developers program its GPUs. A robust developer community programming software for Nvidia’s hardware has helped encourage widespread adoption and make the hardware “sticky.” AI researcher Andrew Ng notes, “I remember at Stanford when my students were telling me, ‘Hey Andrew, there’s this thing called CUDA, …it’s letting people use GPUs for something different.’”

- Don’t discount the value of a little good luck. Nvidia did countless things right—but they still would have died without some good luck. In the late ’90s, Nvidia asked Sega to be let out of a contract for chips so that it could pivot its architecture, but to still be paid in full for the canceled order. Sega’s CEO agreed, even though they got nothing out of it. If he hadn’t, Nvidia wouldn’t have lived to produce the GeForce256, which saved the company.

- Bet on zero-billion dollar markets. Nvidia’s biggest pivots—into 3D graphics for PCs and later into AI—were bets on markets that didn’t yet exist. As board member Mark Stevens puts it, “Jensen always likes to say that, you know, ’We’re investing in zero billion dollar markets.’” This willingness to take calculated risks on unproven markets has been key to Nvidia’s success.

Inside the Episode

The People

Transcript

Chapters

- The story of Nvidia’s founding

- Nvidia’s “Why Now”

- Nvidia's first crucible moment: choosing a zero-billion dollar market

- A failed launch: the NV1

- Nvidia’s partnership with Sega

- One last chance: the Riva 128

- Nvidia introduces the “world's first GPU”

- The pivot to AI

- AI: an unproven market in 2012

- Lessons learned from Nvidia's pivot

Jensen Huang: I was confronted with a situation where we would finish the project and die, or not finish the project and die right away.

Mark Stevens: We were very concerned about, are we gonna lose this company or not?

Jensen Huang: We only got one shot. And if you have one shot, that chip has to be perfect. But how do you build a perfect chip the first time?

Roelof Botha: Welcome to Crucible Moments, a podcast about the critical crossroads and inflection points that shaped some of the world’s most remarkable companies. I’m your host, Roelof Botha.

Almost exactly one year ago, in November of 2022, ChatGPT took the world by storm. Within five days it had 1 million users. Within 8 weeks, 100 million. It was the fastest adoption of a new technology product the world had ever seen.

What fewer people know, however, is the decades-long story of the company that developed the technology that ChatGPT, and much of AI as we know it today, relies on.

Today, we’re looking at Nvidia, the technology company founded in 1993 by Jensen Huang, Chris Malachowsky, and Curtis Priem. Their initial idea was to create 3D graphics cards for gamers. Nvidia’s eventual shift towards AI is one of the most remarkable business pivots in history. It has spotlighted Nvidia on our cultural stage and cemented the company as a global leader in AI computing.

The crucible moments in today’s episode center on Nvidia’s willingness to bet on unproven markets years ahead of time. We’ll look at how Nvidia took a risk at its outset, entering a competitive field and targeting a user base few took seriously. How, days from bankruptcy, they scrapped their product architecture entirely and embarked on a timeline so ambitious no one thought they could pull it off. And how the company, finally dominant in gaming, decided to stake its future on a radically new field that many doubted would ever become a viable market.

The story of Nvidia’s founding

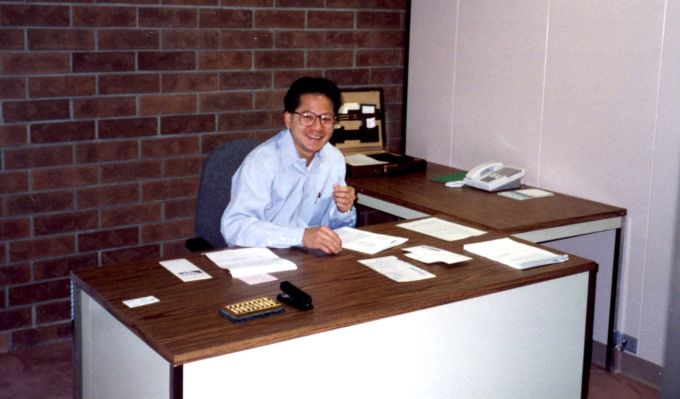

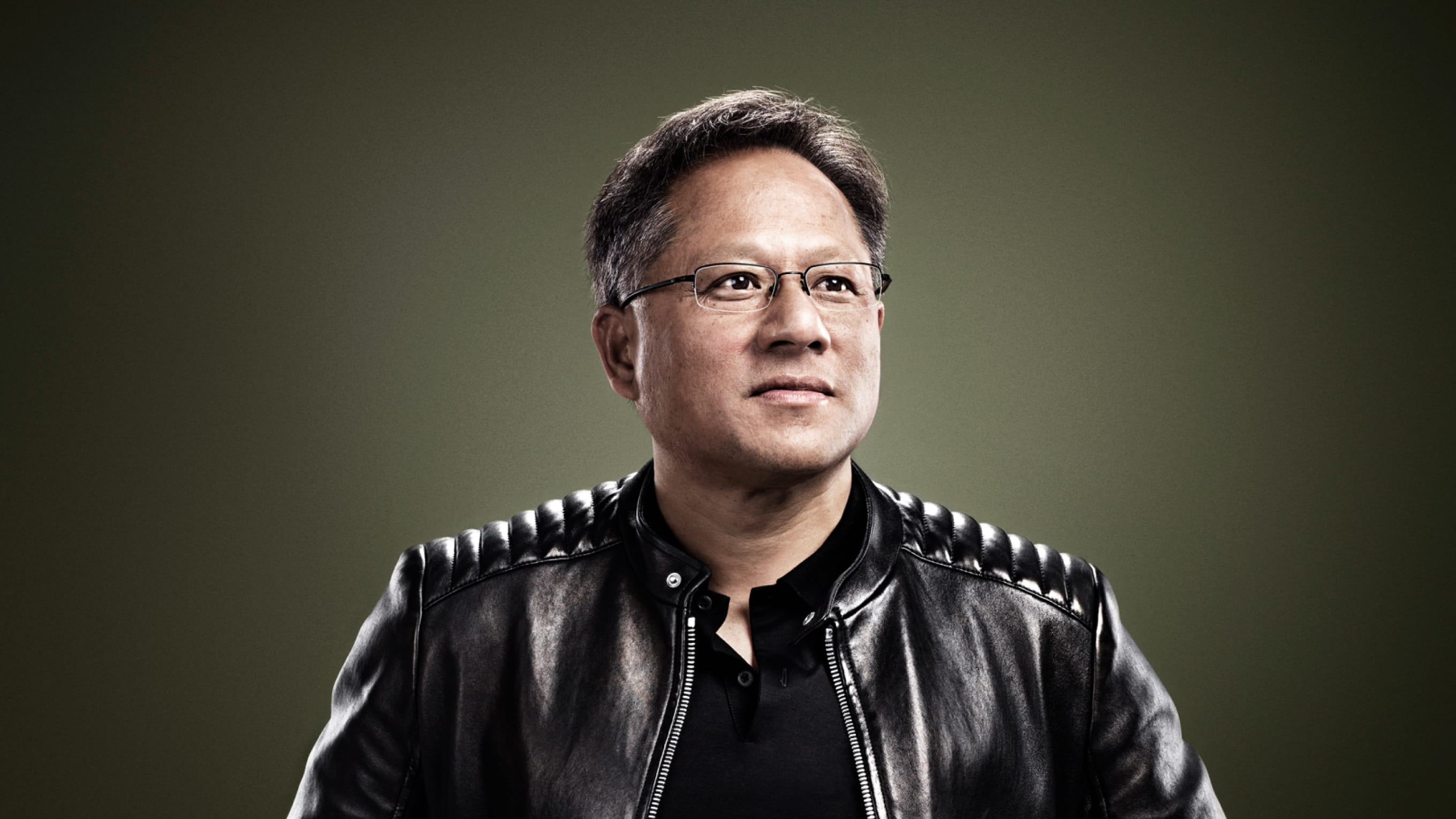

Jensen Huang: I’m Jensen Huang. I’m the President and CEO of Nvidia.

I met Chris and Curtis, they were at Sun Microsystems. I was at LSI Logic. So, we were all from the workstation industry, and all we had ever worked on were Sun workstations, Valiant workstations, and things like that.

Roelof Botha: This was in the 80’s, back when most computers were bulky, expensive machines, really only available to businesses that could afford them. Sun Microsystems manufactured high-end computer workstations, and LSI Logic specialized in semiconductors.

Concurrent with the computer revolution was the race to create the most sophisticated computer chips.

Jensen Huang: Very few companies had the ability to build their own chips, with the exception of IBM, really, at the time. And so Sun was venturing into building semi-custom chips for their computers. Chris and Curtis were building chips at Sun Microsystems. And I was the assigned engineer to work with them from LSI Logic.

Chris Malachowsky: So, in essence, Jensen was assigned to me. And that started a friendship between the three of us.

My name is Chris Malachowsky, I’m Senior Vice President, Fellow, and cofounder of Nvidia Corporation.

Jensen Huang: We really hit it off. Chris and Curtis are two of the best engineers I’ve ever known. Incredible people, visionary in architecture and design. And, I really, really enjoyed working with them.

Roelof Botha: The chips most companies were focused on developing were Central Processing Units, or CPUs—the general-purpose chips that execute commands entered into a computer. But in the early 90’s, Chris, Curtis, and Jensen were tasked with building something more challenging: a Graphics Card, a chip that could be inserted into Sun’s workstations alongside the CPU to render graphics on screen.

Chris Malachowsky: The three of us went about building this graphic subsystem that was challenging. LSI Logic, who had announced they knew how to build chips this size, had never done it. And we were able to get the job done, each sort of staying in our lane and being good at what we did.

Jensen Huang: One year, there were quite a few changes in the computer architecture and the graphics architecture at Sun. And the architecture that Chris and Curtis worked on fell out of favor and they decided to leave the company.

Chris and Curtis reached out to me and asked me if I would like to leave LSI Logic and join them to build a company. And, first of all, none of us knew what company we would build, and I told them that, you know, I wish them well, they’re going to do great. I was gainfully employed and really happy doing what I was doing. They kept asking me and finally I said, “Well, you know, tell you what, why don’t we just go out and we can think through what kind of a company you guys can go build?”

And so we would meet at Denny’s, which is right at the corner of Capitol and Berryessa, this place in East San Jose. I used to wash dishes at Denny’s and I was a busboy at Denny’s and I was a waiter at Denny’s. So I really liked Denny’s. I mean, Denny’s I consider it my first company, you know, and, and so, we would go hang out there. It was always a fun thing for me and a fun thing for them. We’d just sit there and, you know, drink a bunch of coffee and the thing that’s really great about Denny’s is it’s all you can drink.

Chris Malachowsky: We’d show up, we’d order one bottomless cup of coffee. And then, you know, work for four hours.

Jensen Huang: So we just sat there until we ran out of ideas or ran out of things to talk about and go home and, you know, come back and do it again.

Nvidia’s “Why Now”

Roelof Botha: The PC revolution was just beginning in earnest, and the trio recognized this as an important “why now” for their nascent company.

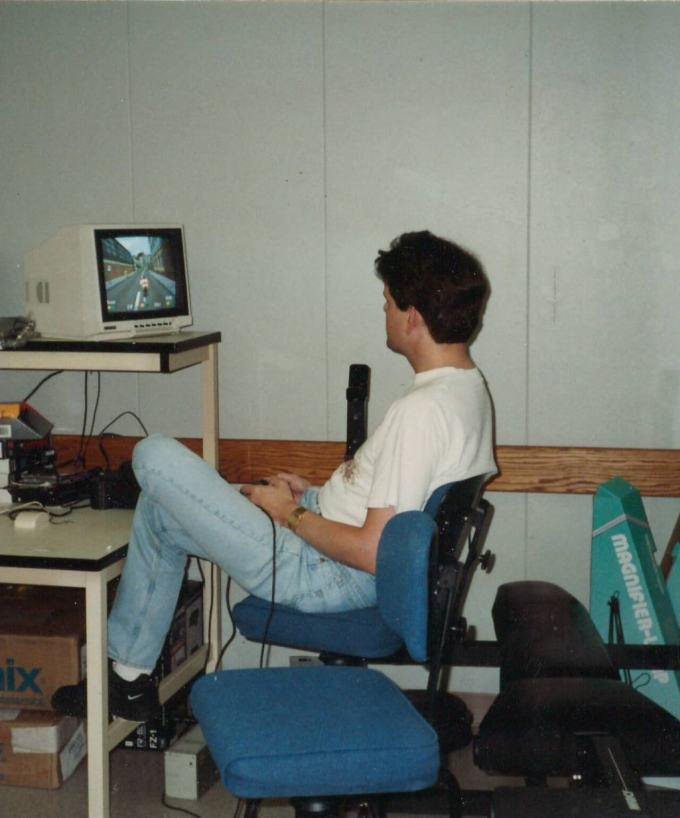

Jensen Huang: This is now 1993; the PC revolution really started in 1995. We knew that the PC was able to reach price points and a level of, of ease of use that might actually have a chance to become, you know, quite pervasive. And so we were excited about the PC revolution. And, we thought, okay, well what application would we bring to the PC and what would we enable as this computer becomes a consumer computer and goes into the home. And what would you do with it? Well, the one thing you would do with it more than anything in the world is play games.

The capability, the graphics capability, the multimedia capability of the PC was non-existent at the time. There were no sounds, there was no microphones, there were no speakers, no video, there’s no graphics. Basically it was a text terminal. And we thought, you know, maybe 3D graphics would be the thing that’d be really cool. And for the very first time, you have a platform that could both be a computer and used for, you know, whatever you want to use it for. You could also use it to play games. And, we just need to go build a chip that makes it possible to play games.

None of us had even seen a PC before. So we had to go buy a PC. We bought a Gateway 2000. Nobody even knows how to program Windows or DOS. Nobody even seen DOS. And so we had to tear it apart, start learning about the industry.

Mark Stevens: If you were to go to market research firms and you asked them, “Well, what’s the market size for 3D graphics for PCs in 1993?” The answer would’ve been zero.

My name is Mark Stevens, I joined Sequoia in 1989 and in 1993 I became the Sequoia representative on the board of directors of Nvidia.

Roelof Botha: Mark has since left Sequoia, by the way, but remains on Nvidia’s board.

Chris, Curtis, and Jensen—who still hadn’t left his job at LSI Logic—wrestled with the idea of launching a company that made 3D graphics chips for personal computers. But they realized if they were to move forward, they would have two major factors working against them. The first was competition.

Mark Stevens: The market for 2D graphics for PCs was crowded at this point. The differentiation here was Nvidia was going after 3D graphics, but there’s a whole raft of chip companies that came out in the 1980s. You had companies like Xilinx and Altera, companies like Cirrus Logic and Chips and Technologies. One could argue, you know, why does, why did the world need Nvidia? Why did the world need another graphics chip company?

Roelof Botha: In addition to a crowded chip market, the second factor working against Nvidia was its target audience and the chip’s intended use.

Mark Stevens: You know, the people who did gaming on PCs up to that point were teenagers.

Chris Malachowsky: Gaming, it just didn’t have a lot of respect. It just didn’t feel like a first-tier business that everybody got and everybody appreciated.

Mark Stevens: And the overall gaming market was much smaller at the time versus the market for movies and other media forms. The gaming market has become huge on a worldwide basis. But back then, gaming on a PC was a fairly small application.

Alfred Lin: Games were just thought of not serious applications.

I’m Alfred Lin. I’m a partner at Sequoia Capital.

Throughout my life, I’ve always been fascinated by Nvidia and fascinated with games, even though I decided not to do any of that professionally. But, I’ve been fascinated with game consoles and the graphics and how you could represent graphics the most efficient way.

I would say a lot of things that don’t seem serious, a lot of things that seem like toys can very much start out that way but, over time, they have this ability to blossom into other applications.

Nvidia's first crucible moment: choosing a zero-billion dollar market

Roelof Botha: The crucible decision for Curtis, Chris, and Jensen was: do you enter a hyper-competitive field of chip making where you have to fight to stand out, and if you do, do you position your innovation as a 3D chip for gamers, an unproven market at the time, and bet on the potential of that market to grow?

Jensen Huang: There are several things that we say in the company and that is: do you believe it or not? The first principles say you start from your assumptions, whatever you believe, and you break it all down, and it says therefore, you should do this, ergo this.

So why don’t you do it? For what reason don’t you do it? And so if you believe this is going to change the computing industry altogether, for what reason don’t you take this first move? Just start.

I think it was, towards the end of 1992, beginning of 1993, that I said, “Okay, Chris and Curtis, I’ll go do it with you guys.” And February 17th, my birthday in 1993, was my first day of work.

Roelof Botha: The founders began looking for investors for their new company, and Jensen went to meet with his old boss, the head of LSI Logic, Wilfred Corrigan.

Jensen Huang: Wilf said, “Look, if you’re going to start a company, go talk to Don Valentine.”

And, while I was sitting there, he picked up the phone and he said, “Hey Don, I’m going to send a kid your way. He’s one of my best employees. I’m not sure what he’s going to do, but give him money.”

I went to Sequoia. Don Valentine was there and he just scares you. You know, I was 29, I had just turned 30. I did a horrible job with the pitch, but thankfully he was already instructed to give me money. Don, at the end, he just said one thing. He said, “If you lose my money, I’ll kill you.”

A failed launch: the NV1

We were working in a small office at a strip mall. I think we probably hired up to 20 people, or something like that. And, here we are, we’re going to build a new chip for a new industry. And so we just started from first principles and started building it up. And we specified this chip called NV1.

Mark Stevens: The NV1 chip was the first device that the company delivered to the market. I believe it took us 18 to 24 months to deliver the chip after the company was founded. And we thought it was gonna be a great chip. The reality is the chip was a failure.

Jensen Huang: It was a great technology achievement. It was a terrible product. You know, when you’re done describing NV1, it sounds like an octopus. Because what kind of a chip does the PC industry buy that has 3D graphics, video processing, audio wave table processing, IO port, game port, acceleration, has this programming model called UDA, no applications that run for it, you know, what do you call this thing? That sounds like an octopus, you know, when you pull it out of the box, it actually comes with these dongles and these dongles makes it kind of feel like an octopus. And you need all these things because you got to, you know, connect the whole computer to it.

Mark Stevens: The way I’ve always thought about it is, we built a Swiss Army knife with lots of functions and the chip was overpriced for what the market wanted. The market wanted a 3D graphics chip and that’s it. And they wanted it as cheap as they could get it and as fast as they could get it. And so, it was a flop.

Jensen Huang: Our customer partner, Diamond Multimedia, we sold them 250,000 in NV1s. The retail sales wasn’t very good. And so Diamond panicked. They returned, basically, most of those products to us. 250,000 units went out. 250,000, well, 249,000 came back. And, practically put us out of business.

Mark Stevens: We learned a lot from that, from that failure. You know, nowadays people refer to this as product-market fit, and so we had a very good product, but the fit was not there vis-a-vis pricing and functionality.

Jensen Huang: I had to learn all of those things. And, you know, how do you position it against the competition? Because the customer’s always thinking of alternatives. And so your PC companies are trying to figure out, okay, so this NV1, you can’t compare it to anything. But it’s not as good as this thing at this. It’s not as good as that thing at that, but it’s incredibly good together. It’s really hard to buy things like that. Nobody goes to the store to buy a Swiss Army knife. It’s something you get for Christmas.

And so in every single way, from product strategy, go-to-market, how to think about the competition, how to think about positioning, how do you even price it? Not to mention, why would you go build such a thing in the beginning? Or there are other ways to go build it? I mean, the list of mistakes that we made, and that I made, in the first three years of the company, you could really write a book.

Mark Stevens: I think the lesson that we learned at Sequoia was that we might have been too early, you know, the investing in the 3D graphics PC market. And that’s always a risk or a fear that we have as early-stage investors. The failure mechanism for most venture-backed technology companies is that they’re too early to market, not too late to market.

We were out there sort of waiting, you know, on our surfboard in the Pacific Ocean, waiting for that big wave, market wave, to come in. And, you know, if the wave never comes in you never get to shore and you freeze to death out in the middle of the ocean.

Nvidia’s partnership with Sega

Roelof Botha: While the failure of the NV1 chip was apparent, there was a bright spot on the horizon: The company was simultaneously developing the NV2 in partnership with the video game company Sega.

Jensen Huang: Sega’s latest game at the time was, you know, Virtua Fighter and Daytona and Virtua Cop and, you know, really, really fantastic 3D-arcade games. They were completely revolutionary.

Sega was also looking for a partner to build their next generation console. And it opened doors for us both in trying to build their next generation console, as well as encouraging them to take the Sega games over to PCs.

Roelof Botha: On the engineering side, the NV1 and NV2 were developed to support an architecture that rendered images using quadrangles. When Nvidia first launched, it was the only company on the market making 3D graphics chips for PCs. But soon, other 3D graphics companies began to emerge. And their chips supported a different type of architecture, one that rendered images using triangles.

Jensen Huang: The architecture we chose was clever at the time, but it turned out to have been the wrong architecture completely. This is 1995, Microsoft had come out with Windows 95, and the API called DirectX is the architecture that everybody else uses except us. We had never even implemented a graphics architecture like DirectX before. And the rest of the industry, now some 50 companies, are all over us. And so the question is, what do we do?

If we had finished that game console with Sega and fulfilled our contract, we would have spent two years working on the wrong architecture while everybody else is racing ahead in this new world that, quite frankly, we kind of started.

On the other hand, if we didn’t finish the contract, then we run out of money. And so I was confronted with a situation where we would finish the project and die, or not finish the project and die right away.

Roelof Botha: Your first chip is a failure and your second chip is doomed. Nvidia had arrived at a crucible moment. Do you finish the job you started and hope the revenue can sustain you? Or do you break your contract, scrap your entire architecture, and start from scratch?

Jensen Huang: This existential moment for our company was pretty difficult. You know, heated discussion among us to try to figure out what to do.

And I think the final decision was the right one, which is, we have to figure out what is the right path forward long term and work our way back. And the long term answer, of course, is we have to support this new architecture, this new graphics architecture, it’s called inverse texture mapping. And, we have to abandon the forward texture mapping architecture that we had started. And whatever we have to do to achieve that is the right thing to do.

So I went to Sega and to the credit of their CEO, Irimajiri-san, I told him our circumstance is that if we finish this game console for you, our company would be out of business. And, quite frankly, I think that this architecture that we would build for you would be the wrong architecture because the world is moving towards this other approach called inverse rendering, inverse texture mapping.

He asked me what I’m asking him to do. And so I told him that, although there’s no reason for him to do this, I would like him to let us off of our contract, relieve us of our responsibility of fulfilling the contract, but pay us in full. And, they got absolutely nothing out of it. There was no reason for him to do it. And, he thought about it for a couple days. He, you know, came back to me and, and said, I’d like to help you.

You can’t discount the kindness of people when you’re starting your company, when you benefit from the kindness of all the people that support you. But in this particular case, it was some 5 million dollars, I think it was, that they continued to pay us. It was all the money that we had. And it gave us just enough money to hunker down.

Mark Stevens: After the failure of NV1 and then after NV2 sort of being abandoned, we were very concerned as investors. You know, at this point we’re probably three years into the company, something like that. And it wasn’t clear if Nvidia was ever gonna, sort of, have escape velocity.

One of the things that Jensen, he said this for many, many years, was, “We’re only 30 days away from going outta’ business.”

Well, the fact of the matter is, on a few occasions in the mid-nineties, that was true from, you know, ‘cause we were burning cash and developing these graphics devices, you needed some of the best hardware in silicon engineers in Silicon Valley. And, these folks do not come cheaply especially when we were competing with Silicon Graphics, which was a sort of a juggernaut at the time for engineering talent, and Apple at the time. So, we were very concerned about are we gonna lose this company or not?

Roelof Botha: With the last of their resources, the company mounted one more attempt at a breakthrough chip.

One last chance: the Riva 128

Jensen Huang: We only got one shot. And if you have one shot, that chip has to be perfect. But how do you build a perfect chip the first time? Nobody knew how to do that. Because in the old days, you would build a chip, bring it up, write software for it, find bugs, iterate the chip, tape it out again, bring up more software until you get it done. So tape out to production was, oftentimes, at least a year, year and a half. I told the team that, look, we get one tapeout. And they said, “Why?”

Because if we need more than one tapeout, we don’t need it. We’ll be out of business. And so we get one shot.

Mark Stevens: In times of crisis is when real quality CEOs are on display. And this was a time where we, as investors and board members, discovered that Jensen was really unique in the way he managed a crisis.

Jensen Huang: I said let’s work backwards. If we get one shot, what do we have to do to make sure that that one shot was perfect? And so we have to do all the software in advance, we have to do everything in advance. And we did it in about six to seven, eight months. And on complete fumes.

And there was this other company that went out of business at the time, and I’d heard about it, it’s called Icos. And Icos had built this thing called an emulator. An in-system emulator. We called Icos. They said thanks for calling, but we’re out of business. And I said, “Really? That’s insane. We really could use one of your instruments.” It’s the size of a refrigerator. You plug it into the PC that you want to emulate for, and you pretend, it’s called emulation, you pretend like you’re the final chip.

And he says, we have one in the warehouse, you know, it’s an inventory. If you want it, we’ll sell it to you. And so we bought the scraps out of a company that was going out of business.

And we emulated RIVA 128 NV3, the first PC chip the world’s ever emulated. And, we taped out the chip, and the chip worked the first time.

Unsurprisingly, to me, anyhow, that the genius of the people that were at Nvidia would come up with the world’s best inverse texture mapping engine and completely crushed everyone and revolutionized what we know today about modern computer graphics. We changed the way that chips were designed. We changed the way that you tapeout chips. The way almost everything about our company today. Yeah, we saved the company.

Roelof Botha: The Riva 128 was a feat of engineering, and in its first four months sold 1 million units. Even more importantly, the expedited process of building and testing the Riva allowed Nvidia to then launch its next chips at a cadence more than twice as fast as competitors.

Alfred Lin: At the beginning, Nvidia was behind, but soon, probably soon after 1999, they were just far ahead of their competition. And you can just see it. So when Quake III Arena came out in 1997, you just could see how much better the Nvidia chips performed against others.

Nvidia introduces the “world's first GPU”

Roelof Botha: Nvidia’s fifth chip was its first programmable chip. It was called the GeForce 256.

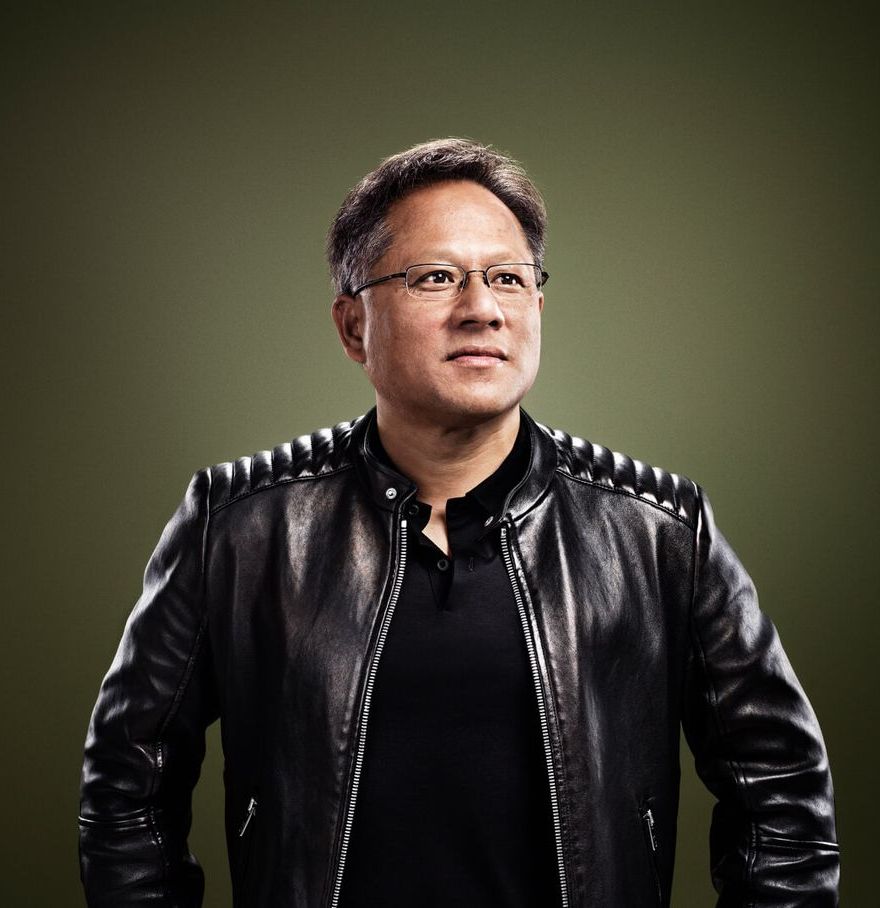

Jensen Huang: That was the world’s first GPU. And that was adding programmability to acceleration. So we created the world’s first programmable accelerator. A programmable accelerator is accelerated computing. And the benefit of an accelerator is whatever you designed it to do, it does it incredibly efficiently. And so, no matter how effective a CPU is, with a programmable accelerator you could be a thousand times more effective.

Roelof Botha: This programmability would prove critical to the company’s next chapter, but it also paid immediate dividends. With programmable shaders enabled by GeForce GPUs, video games exploded in creativity and popularity. Nvidia went public in 1999 and, in a twist of fate, Microsoft—whose DirectX architecture nearly sidelined Nvidia in its early years—chose GeForce to power its new project: the Xbox.

Alfred Lin: It took five generations for them to get this graphics acceleration right before they produced their first GPU. And so the company was founded in 1993 and I don’t think they released the GeForce 256 until late 1999. So it was a long time of just iterating, iterating, iterating until they got it right to produce the first GPU unit.

If you solve really hard problems that nobody else can solve, which is what Nvidia has done, and you’re patient, you can build a tremendous company over time.

The pivot to AI

Roelof Botha: The success of the GeForce carried Nvidia into the mid 2000’s. But, as with all companies that break new ground, eventually competitors catch up. And while Nvidia had solidified its position as a major player in the 3D graphics market for PC games, over time, its singularity, its shine, began to fade.

Mark Stevens: The PC market at that point was starting to asymptote in growth, and we were worried about that. And since we were selling into the PC, we still had to contend with Intel as a competitor, AMD to some extent. And so we felt we were always gonna be sort of boxed into the PC gaming market and always knocking heads with Intel if we didn’t develop a brand new market that nobody else was in.

Nvidia had invented the GPU. And it was a programmable device, which means that it could be programmed and adapted for applications outside of gaming.

Roelof Botha: The 2006 release of CUDA, a general purpose programming interface for Nvidia’s GPUs, opened the door for use cases far beyond gaming.

Jensen Huang: Molecular dynamics, seismic processing, CT reconstruction, image processing—a whole bunch of different things.

Chris Malachowsky: I remember starting to hear, and musing about, a lot of graduate students for their research found these, you know, graphics chips at their local electronics store and they were writing simulators on them and doing research on them.

Jensen Huang: Universities after another, researchers realized that by buying this gaming card called GeForce, you add it to your computer, you essentially have a personal supercomputer.

One of the scientists that I saw was in Taiwan. And he was a quantum chemist and I was in Taiwan at the time and he reached out to me and said, you know, “Come and see something.” And I went to NTU, National Taiwan University and he opened his closet and there was this giant array of GeForce cards sitting on all these shelves with these house fans rotating. And he said, “I built my own personal supercomputer.” And, and he said to me that because of our work, because of your work, he’s able to do his work in his lifetime.

And, simultaneously, Andrew Ng was working on deep learning at the time.

Andrew Ng: So around 2008, 2009, my students and I started to work on and push the idea that GPUs could be used for deep learning, for neural networks.

Hi, my name is Andrew Ng. I’m managing general partner of AI Funds, a venture studio, and I also lead DeepLearning.AI and Landing AI.

You know, neural networks have been around for a long time, for many decades, and so have GPUs. But I think the convergence of these two ideas came for a couple of reasons.

One is we finally had enough data that we needed that compute to feed into neural networks.

And then there was one other breakthrough technology. I remember at Stanford when my students were telling me, “Hey Andrew, there’s this thing called CUDA, not that easy to program, but it’s letting people use GPUs for something different. Could we build a server to use GPUs and see if they could scale-up deep learning?”And, one of my students at the time, Ian Goodfellow, who was my undergrad, helped me build a GPU server in his dorm room. And that server wound up being what we used for our first deep learning experiments to train neural networks.

We started to see 10x or even 100x speedups training neural networks on GPUs because we could do a thousand or 10,000 things in parallel, rather than one step after another.

That’s a total game changer for what you can do with neural networks.

Jensen Huang: Meanwhile, in Toronto, Canada, Hinton’s lab was doing the same thing. Yann LeCun’s lab in New York University was doing the same thing. They all kind of simultaneously reached out to us and we realized that maybe there’s a new type of computing model that we could create.

Roelof Botha: This was just before AlexNet—the first breakthrough in computer image recognition in 2012—and years before AlphaGo. AI was still a niche pursuit.

AI: an unproven market in 2012

Mark Stevens: The biggest risk of trying to pursue the AI market was very similar to the risk the company had encountered back at its founding. The market for AI chips in 2012, 2014, 15. It was a zero billion dollar market. And Jensen always likes to say that, you know, “We’re investing in zero billion dollar markets.”

This would be spending R&D dollars on a market that may never materialize. There was no guarantee that AI would ever really emerge because, keep in mind, AI had had many stops and starts over the last 40 years. I mean, AI has been around as a computer science concept for decades. But it had never really taken off as a huge market opportunity.

Jensen Huang: This is the type of risk that, unless you’ve survived building a startup, you’re probably allergic to doing. And the reason for that is at this time, we’re public, we’re a multi billion dollar company, we’re actually successful now. And, you know, we’ve dodged several life-threatening challenges. Nobody wants to derail the company. They want to defend the company and protect the company.

Roelof Botha: Success can make you risk-averse. For two decades, Nvidia had been synonymous with chips for gaming on PCs. Should the company stay in its lane, or stake their future on a market that was unproven, but which leadership and researchers around the world felt had enormous potential?

Chris Malachowsky: At some point somebody said, “You know, this actually is a way to expand the market.” There’s a lot of opportunity for computation that wasn’t strictly put a color up on the screen. So in order to capture that and maybe take advantage of this growing, undercurrent of desire to get access to this, you know, Jensen and the team were willing to go for–a zero billion dollar business–on the hopes. Because you got to believe what you got to believe and then you put your money where your mouth is. So if we thought this was likely to be an important segment of the market that we could tap into that we could grow our TAM into, then you do it.

You know, I credit a lot of people, not me, with the courage to just go do it. And, let’s see where it takes us.

Roelof Botha: Nvidia made a crucible decision that would change not only its own trajectory but that of the entire technology industry. They would commit to AI computing.

Lessons learned from Nvidia's pivot

Jensen Huang: This was a giant pivot for our company. We’re adding cost, we’re adding people, we have to learn new skills. It took our attention away from our normal day-to-day competition in computer graphics and gaming. The company’s focus was steered away from its core business. And it wasn’t just in one place, it’s all over the company. It was a wholesale pivot in this new direction.

Andrew Ng: To Jensen’s credit, I saw him leap early and place a very significant bet. He started to allocate more resources to it pretty quickly. I was impressed that the CEO of a large company, that he saw it clearly enough to commit his company to this direction early.

Jensen Huang: As a CEO or anybody who is trying to steer the ship in a new direction, you have to have some intermittent, some near-term positive reinforcements. And so you have to keep promoting the idea. Whenever something good happens, that reinforces the direction you’re going you have to, you know, put into perspective: What is this? Why is this important? How does this help us get to the next level?

When we pivoted the ship in that direction, we sought out every single AI researcher on the planet. And our platform being useful to them was the positive feedback that we were getting at the time. Which is the reason why I’m friends with, you know, all of the world’s great AI researchers. They were all helpful in providing the early indications of future success along the way for me and, you gotta make a big deal out of those small wins.

Mark Stevens: I think we realized that Nvidia was the spearhead of the AI revolution really within the last two to three years. We saw our GPUs being adopted by large-scale data centers and cloud service providers. And we began to see the applications again in transportation, healthcare. That was really when we discovered, hey, this is going to be a very diverse and a multi-billion dollar opportunity that had, you know, 10 years or 15 years in front of it.

Jensen Huang: For the last 30 years or so, the computer industry has been advancing at about 10 times every 5 years: Moore’s Law.

Roelof Botha: Moore’s Law is the famous prediction that CPU performance will double roughly every two years, or 10 times every five years.

Jensen Huang: Now with AI, we’re advancing at the chip level, at the system level, at the algorithm level, and also at the AI level. And so, because you have so many different layers moving at the same time, for the very first time we’re seeing compounded exponentials. And, if you go back and just look at what, how far we’ve gone since ImageNet, AlexNet, we’ve advanced computing by about a million times. Not a thousand times. A million times. Not a hundred times. A million times. And we’re here now compounding at a million times every ten years.

Roelof Botha: This new pace at which computing is advancing—a million times every ten years—has been affectionately dubbed “Huang’s Law.”

Jensen Huang: And so the question is, what can you solve in the past that you were waiting for a million times to solve? A problem that you thought, you know, I could solve this probably in about thirty years. Well, if you can solve it in about thirty years, you’re probably going to solve it in five. That’s the big realization. That’s groundbreaking. That’s really the reason why I think it’s an inflection point. Things that look far on the horizon, you really, really ought to think about it. Not in decade time frame, but in years time frame.

Roelof Botha: Nvidia’s acceleration of computing now includes a platform for transforming data centers and cloud computing, and extends beyond AI to anything that can be simulated. As Jensen looks to the future, Nvidia is already building hardware and software for everything from digital twins to climate modeling to drug discovery.

Chris Malachowsky: Everybody suddenly wants to know where we came from. I find it humorous that, where the hell did these guys come from? We thought they were just gaming. And suddenly the CUDA stuff, it allowed us to make a difference in markets that weren’t gaming, which I think then helped people value the fact that gaming was such a strong market and such a economically large market.

We did what was necessary to continue to move the needle, stay in business long enough to let the ideas come together. I met somebody the other day and she said, “Oh, how do you feel about your success?”

And I said, “Well, it feels like this overnight success was 30 years in the making.”

Roelof Botha: There’s a concept we talk about at Sequoia called the “timespan of discretion.” What is the time scale across which you operate? How do you stretch your imagination to make an enduring impact? No founder has embodied this notion like Jensen.

It’s been 30 years since Nvidia launched. Not many of us think in 30-year timeframes. And paradoxically, by seeing its decades-long vision through to fruition, today Nvidia’s technology is enabling us to accomplish far more in far less time.

Jensen Huang: Every CEO’s job is supposed to look around corners. By definition, we should be able to connect more dots. The CEO also has to be the most bold about what opportunities, what problems we can go solve that nobody imagines us solving. You want to be the person who believes the company can achieve more than the company believes it can.

When you’re a startup CEO, you’re zero and you’re trying to become something more than that. The idea that you would be a global-anything is insanely ambitious. By almost all measures, we shouldn’t be here.

There are only so many diving catches you can make in life. And it’s not just—diving catch doesn’t mean luck. It does require a lot of effort. You have to realize it’s existential. You have to be surrounded by amazing people. And the people that did those diving catches, many of them, most of ‘em are still here. And so it’s pretty amazing.

Roelof Botha: This has been Crucible Moments, a podcast from Sequoia Capital. We’ll be back with season 2 next year.

If you have an idea for a company we should feature, questions about company-building or any feedback on the show, we’d love to hear from you. Email us at ideas@cruciblemoments.com.

In the meantime, keep an eye out for bonus material coming soon. Thanks for listening.